80k After Tax UK: 2024/25 Take-Home Pay & Salary Guide

This guide is focused on the UK PAYE system (employees) and shows England/Wales/Northern Ireland figures first, then highlights Scotland where income tax bands differ.

Quick Snapshot: How Much Is £80,000 After Tax in the UK (2024/25)?

If you earn £80,000 a year as an employee under the UK PAYE system, your actual take-home pay will be significantly lower than your gross salary. This is because income tax and National Insurance contributions are deducted before your salary reaches your bank account.

For the 2024/25 tax year, assuming you are based in England, Wales, or Northern Ireland, are employed under PAYE, and have a standard tax code of 1257L (which means you are entitled to the full £12,570 Personal Allowance), your approximate take-home pay is as follows — provided there are no additional deductions.

These figures assume:

- one PAYE employment

- no pension contributions (including salary sacrifice)

- no student loan repayments

- no taxable benefits-in-kind (such as a company car or private medical insurance)

- no High Income Child Benefit Charge (HICBC)

Under these assumptions, your £80,000 salary after tax in the UK is approximately:

- Annual net pay: £56,957

(often shown as £56,956–£56,958 depending on payroll rounding across monthly or weekly pay cycles) - Monthly take-home pay: around £4,746

- Weekly take-home pay: around £1,095

- Daily take-home pay: around £219, based on a simple five-day working week for budgeting purposes

This means that, in practice, around 71% of your gross salary reaches you as net income, while approximately 29% is deducted through income tax and employee National Insurance contributions.

Learn more about the UK PAYE system on our page about personal tax self-assessment services.

Where do these deductions come from?

The difference between your £80,000 gross salary and your £56,957 take-home pay is driven by two main deductions applied through PAYE:

- Income Tax – approximately £19,432

- The first £12,570 of your income is tax-free under the Personal Allowance.

- Income between £12,571 and £50,270 is taxed at the basic rate of 20%.

- Income above £50,270 (up to £80,000 in this case) is taxed at the higher rate of 40%.

These progressive tax bands mean that not all of your salary is taxed at 40%, even though you are classed as a higher-rate taxpayer.

- Employee National Insurance (Class 1) – approximately £3,611

- National Insurance is charged at 8% on earnings between the Primary Threshold and the Upper Earnings Limit.

- Earnings above the Upper Earnings Limit are charged at a reduced rate of 2%.

Although National Insurance is often overlooked, it still reduces take-home pay by around £300 per month at an £80,000 salary level.

Why this “Quick Snapshot” is only a starting point

While these figures provide a reliable benchmark for “80k after tax UK” calculations, many people earning £80,000 will see lower take-home pay in reality.

Common reasons include:

- workplace pension contributions

- student loan repayments

- High Income Child Benefit Charge for families

- Scottish income tax rates (which are higher)

- taxable benefits and adjustments to tax codes

This is why two people earning the same £80,000 salary can receive very different net pay.

Which Tax Year Should This Page Use: 2024/25 or 2025/26?

When discussing UK salaries, tax, and take-home pay, one of the most important — and most frequently misunderstood — details is the tax year being used.

In the UK, tax is not calculated by calendar year. Instead, the UK operates a fixed tax year that always runs from 6 April to 5 April the following year. All PAYE calculations, payroll deductions, tax thresholds, and National Insurance contributions are tied to this structure.

For clarity:

- 2024/25 tax year:

Runs from 6 April 2024 to 5 April 2025 - 2025/26 tax year:

Runs from 6 April 2025 to 5 April 2026

This distinction matters because even when tax rates remain unchanged, thresholds, allowances, and contribution rules can differ between tax years — which directly affects take-home pay.

Why this article is based on the 2024/25 tax year

This guide is intentionally written around the 2024/25 tax year, for two key reasons:

- Accuracy of benchmark figures

The core figures people search for — such as “80k after tax UK”, “80,000 salary take-home pay”, and “80k take home pay UK” — are currently based on 2024/25 PAYE thresholds. Using this year ensures that the calculations shown reflect what most UK employees are actually seeing on their payslips right now. - Alignment with payroll reality

Most UK payroll systems apply the current tax year’s rules automatically. For the majority of employees reading this guide during the 2024/25 period, their monthly net pay is being calculated using 2024/25 PAYE tax bands and National Insurance thresholds. Presenting figures from a future year too early would risk confusion rather than clarity.

Why 2025/26 is still relevant — and included later in the article

Although the primary calculations use 2024/25, it would be incomplete — and professionally irresponsible — to ignore upcoming changes.

That is why this guide also includes a forward-looking section on 2025/26, focusing on areas that can materially affect higher-rate earners, such as:

- continued freezing of income tax thresholds (fiscal drag)

- changes to employer National Insurance costs

- indirect impacts on salary reviews, bonuses, and employment structures

This approach strikes a balance between current accuracy and future awareness — allowing readers to understand both their present take-home pay and the direction of travel.

Why official payroll thresholds matter more than “headline tax rates”

Many people assume that tax planning revolves only around income tax rates (20%, 40%, 45%). In practice, thresholds and limits are just as important — especially at higher incomes.

This is why official payroll guidance published by GOV.UK is used as the primary reference point throughout this article.

In particular, the GOV.UK publication “Rates and thresholds for employers 2024 to 2025” is one of the most reliable and practical sources because it brings together:

- PAYE income tax thresholds

- National Insurance contribution limits

- employee and employer NIC rates

- the exact figures used by payroll software

Using these sources ensures that the calculations shown in this guide match real-world payroll outcomes, not theoretical estimates.

80k After Tax UK: Detailed Annual & Monthly Calculations (2024/25)

This section shows the baseline PAYE calculation for an employee earning £80,000 per year in England, Wales, or Northern Ireland during the 2024/25 tax year.

It represents the simplest and most commonly searched scenario and forms the reference point for all further variations discussed later in this guide.

Assumptions used in this calculation

The figures below assume:

- one PAYE employment

- tax code 1257L (full Personal Allowance available)

- no pension contributions (including no salary sacrifice)

- no student loan repayments

- no taxable benefits-in-kind

- no High Income Child Benefit Charge (HICBC)

Any deviation from these assumptions will change the final take-home pay, sometimes significantly.

Step A — Start with gross salary

The calculation begins with the contractual gross salary:

- Gross annual salary: £80,000

This is the headline figure stated in the employment contract and the amount used by payroll before any deductions are applied.

Step B — Apply the Personal Allowance (tax-free income)

Under the UK income tax system, most individuals are entitled to a Personal Allowance, which represents the portion of income that is not subject to income tax.

For the 2024/25 tax year, the standard Personal Allowance is:

- £12,570

A tax code of 1257L indicates that the full allowance is available and that there are no adjustments for benefits, underpaid tax, or multiple employments.

After applying the Personal Allowance, only the remaining income is subject to income tax:

- Taxable income = £80,000 − £12,570 = £67,430

This figure is the starting point for applying the UK income tax bands.

Step C — Calculate Income Tax using UK bands (non-Scotland)

Income tax in England, Wales, and Northern Ireland is charged using progressive tax bands, meaning different portions of income are taxed at different rates.

The standard UK income tax bands for 2024/25 are published by GOV.UK and are applied automatically through PAYE payroll systems.

For this tax year:

- 20% basic rate applies to taxable income from £12,571 to £50,270

- 40% higher rate applies to taxable income above £50,270, up to £125,140

Applying these bands to the taxable income of £67,430:

Basic rate portion

- Amount taxed at 20%: £37,700

- Tax due: £37,700 × 20% = £7,540

Higher rate portion

- Remaining taxable income: £67,430 − £37,700 = £29,730

- Tax due: £29,730 × 40% = £11,892

Total income tax

- £7,540 + £11,892 = £19,432

Although the individual is classed as a higher-rate taxpayer, only the portion of income above the basic-rate limit is taxed at 40%.

Step D — Calculate employee National Insurance (Class 1)

In addition to income tax, employees pay Class 1 National Insurance contributions, which are deducted through PAYE.

For 2024/25, employee National Insurance operates using two main rates:

- 8% between the Primary Threshold and the Upper Earnings Limit

- 2% on earnings above the Upper Earnings Limit

The annual thresholds used by payroll systems are:

- Primary Threshold: £12,570

- Upper Earnings Limit: £50,270

Applying these thresholds to an £80,000 salary:

NIC at 8%

- Earnings between £12,570 and £50,270: £37,700

- NIC due: £37,700 × 8% = £3,016

NIC at 2%

- Earnings above £50,270: £29,730

- NIC due: £29,730 × 2% = £594.60

Total employee National Insurance

- £3,016 + £594.60 = £3,610.60

In practice, payroll systems often round this figure slightly, which is why payslips commonly show £3,611 or £3,612 as the annual NIC deduction.

Step E — Calculate take-home pay (net pay)

Finally, take-home pay is calculated by deducting income tax and employee National Insurance from the gross salary:

- Net pay = £80,000 − £19,432 − £3,610.60

- Net annual pay = £56,957.40

This is why most authoritative UK salary guides and payroll calculators cite an £80,000 after tax UK figure of approximately £56,956–£56,958, depending on rounding and pay frequency.

This net amount forms the baseline against which all further deductions and planning scenarios in this article are measured.

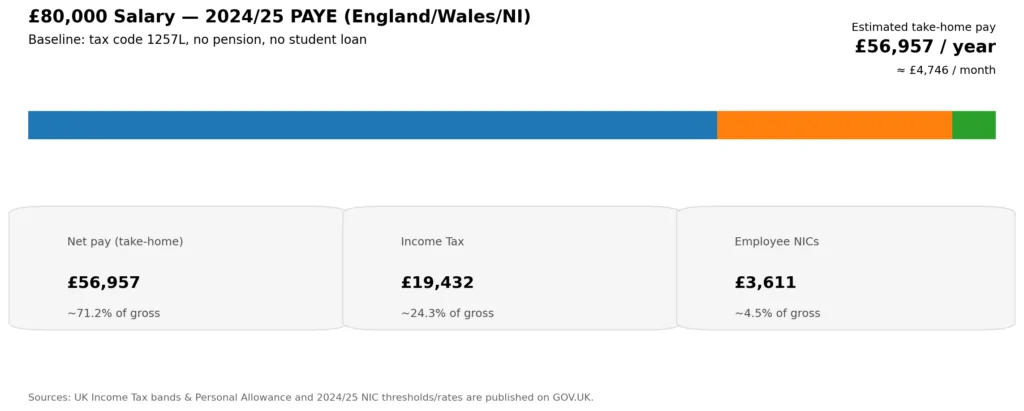

Table: £80,000 salary take-home pay (England/Wales/NI, 2024/25 baseline)

| Period | Gross Pay | Income Tax | Employee NICs | Net Pay (Take-home) |

| Annual | £80,000 | £19,432 | ~£3,611 | ~£56,957 |

| Monthly (÷12) | £6,666.67 | £1,619.33 | ~£300.88 | ~£4,746 |

| Weekly (÷52) | £1,538.46 | £373.69 | ~£69.43 | ~£1,095 |

| Daily (weekly ÷5) | £307.69 | £74.74 | ~£13.89 | ~£219 |

Note: monthly/weekly values can vary slightly depending on how payroll rounds NICs each period.

Infographic (ready to embed): “Where your £80,000 goes” (baseline PAYE)

Data source references (for compliance / trust):

- PAYE tax rates & thresholds + NIC thresholds and 2024/25 employee rates: GOV.UK employer rates and thresholds guidance. GOV.UK

- Income Tax bands overview: GOV.UK.

Infographic (ready to embed): “Where your £80,000 goes” (baseline PAYE)

Looking for a Stress-Free Way to Manage Your Higher-Rate Taxes?

Earning £80,000 a year places you firmly into higher-rate tax territory, where the UK tax system becomes noticeably more complex. At this income level, your take-home pay is influenced by far more than just headline tax rates. Payroll deductions, National Insurance, student loans, pension structures, and household-level charges such as the High Income Child Benefit Charge can all materially affect your real income.

Many higher-rate taxpayers are surprised to discover how easily small oversights — an incorrect tax code, poorly structured pension contributions, or missed reliefs — can result in overpaying tax year after year.

At Audit Consulting Group, we help bring clarity to this complexity. Our role is to ensure that your tax position is fully understood, correctly structured, and aligned with HMRC rules — so you can make confident decisions about your income, savings, and long-term plans.

We support UK employees, contractors, and company directors with:

- higher-rate personal tax planning

- PAYE and payroll-related queries

- pension and salary sacrifice optimisation

- student loan and Child Benefit considerations

- Self Assessment and HMRC compliance

Our approach is practical, transparent, and tailored to your circumstances. We focus not just on calculations, but on helping you understand why your take-home pay looks the way it does — and what can be done, legally and responsibly, to improve your position.

Don’t leave your take-home pay to chance. Professional guidance at the right time can make a meaningful difference to both your cash flow today and your financial position in the years ahead.

Contact Audit Consulting Group

Phone: +44 7386 212550

Email: info@auditconsultinggroup.co.uk

Website: https://auditconsultinggroup.co.uk

If you’d like a callback, simply fill out our contact form and a member of our team will be in touch.

How Is £80,000 After Tax Calculated? UK Tax Bands Explained

To understand how £80,000 after tax in the UK is calculated, it’s essential to first understand how the UK income tax system works at a structural level.

The UK uses a progressive income tax system. This means that your entire salary is not taxed at a single flat rate. Instead, different portions of your income are taxed at different rates, known as tax bands. Each band applies only to the slice of income that falls within it.

This distinction is critical, because misunderstandings around tax bands are one of the main reasons people searching “80k after tax UK” overestimate how much tax they expect to pay.

UK income tax bands (England, Wales, Northern Ireland)

For most UK residents (excluding Scotland, which has its own system), the standard income tax bands for the 2024/25 tax year are as follows, as published by GOV.UK:

- 0% on income covered by the Personal Allowance (up to £12,570)

- 20% on income from £12,571 to £50,270 (basic rate)

- 40% on income from £50,271 to £125,140 (higher rate)

- 45% on income above £125,140 (additional rate)

Each rate applies only to the income within that specific range, not to your entire salary.

Why £80,000 is taxed the way it is

At a salary of £80,000, you are firmly classed as a higher-rate taxpayer, because part of your income falls into the 40% band. However, this does not mean that your whole £80,000 is taxed at 40%.

Instead:

- the first part of your income is tax-free

- the next portion is taxed at 20%

- only the top slice is taxed at 40%

This is where many people feel surprised. They hear “40% tax” and assume their tax bill must be close to £32,000 (40% of £80,000). In reality, the tax bill is much lower because the earlier portions of income are taxed at 0% and 20%, not 40%.

Understanding this “layered” approach is the key to understanding all UK take-home pay calculations.

Understanding the 1257L tax code and the Personal Allowance

Most UK employees with a single job and no unusual circumstances are on the tax code 1257L.

This code indicates that:

- you are entitled to the standard Personal Allowance

- the allowance amount is £12,570

- there are no adjustments for benefits, underpayments, or multiple income sources

The Personal Allowance represents the portion of income you can earn without paying any income tax. It is applied before tax bands are considered and forms the foundation of all income tax calculations.

When your Personal Allowance may change

Your Personal Allowance — and therefore your tax code — is not fixed for life. It can be adjusted by HMRC if:

- you receive taxable benefits such as a company car or private medical insurance

- you underpaid tax in a previous year and HMRC is recovering it

- you have more than one job or pension at the same time

- HMRC estimates future tax adjustments and builds them into your code

Even relatively small adjustments to your tax code can change your net pay noticeably. For someone earning £80,000, a different tax code can shift take-home pay by hundreds or even thousands of pounds per year.

This is one of the reasons why two people on the same salary may see very different net figures on their payslips.

The impact of the 40% higher-rate band at £80,000

For the 2024/25 tax year, the higher-rate band begins once your taxable income exceeds the basic-rate limit. When combined with the Personal Allowance, this corresponds to a gross salary threshold of £50,270.

At an £80,000 salary:

- the portion of income taxed at the higher rate is £29,730

- that slice alone generates £11,892 of income tax

This higher-rate slice is the main driver of the jump in total tax liability once earnings move beyond £50,270.

Why £80k often feels like a “tax cliff”

Although the system is progressive, the experience at £80,000 can feel abrupt. Once you cross into higher-rate territory:

- marginal income tax increases to 40%

- employee National Insurance still applies

- student loan repayments may continue

- household charges such as HICBC can be triggered

As a result, each additional pound of income can be reduced much more heavily than at lower salary levels. This sharp rise in marginal deductions is why £80k salary after taxes often feels like a turning point — not because the system suddenly becomes unfair, but because multiple mechanisms start operating at once.

National Insurance and £80,000 After Tax UK Deductions

When calculating £80,000 after tax in the UK, many people focus almost entirely on income tax. However, income tax is only part of the picture. The second major deduction applied through PAYE is National Insurance, specifically Class 1 National Insurance contributions for employees.

Although National Insurance is often perceived as a smaller or secondary charge, it plays a crucial role in reducing take-home pay at higher income levels and significantly affects how additional earnings are taxed.

How employee National Insurance works (Class 1)

For the 2024/25 tax year, employee National Insurance is calculated using a tiered structure similar to income tax. The applicable rates and thresholds are published by GOV.UK and are embedded into all UK payroll systems.

For employees, the key rates are:

- 8% on earnings between the Primary Threshold and the Upper Earnings Limit (UEL)

- 2% on earnings above the Upper Earnings Limit

The annual thresholds used by payroll are:

- Primary Threshold: £12,570

- Upper Earnings Limit: £50,270

These thresholds align closely with the income tax Personal Allowance and basic-rate limit, which often leads people to assume that National Insurance “stops” at higher incomes. In reality, it continues — just at a lower rate.

National Insurance on an £80,000 salary

Applying the 2024/25 NIC structure to an £80,000 salary:

- Earnings between £12,570 and £50,270 (£37,700) are charged at 8%

- Earnings above £50,270 (£29,730) are charged at 2%

This results in total employee National Insurance of approximately £3,610–£3,612 per year, depending on payroll rounding.

In monthly terms, this equates to roughly £300–£301 per month being deducted from gross pay purely for National Insurance.

Why National Insurance matters at £80,000

While National Insurance is smaller than income tax in absolute terms, it becomes particularly important at higher income levels because of its interaction with income tax.

Above the Upper Earnings Limit:

- income tax is charged at 40%

- employee National Insurance is charged at 2%

This creates a combined marginal deduction rate of approximately 42% on each additional pound earned above £50,270 — before considering student loans, pension contributions, or household-level charges.

This “double marginal” effect explains why:

- bonuses can feel heavily taxed

- pay rises above £50,000 often feel less rewarding than expected

- higher-rate earners are especially sensitive to how additional income is structured

Understanding this interaction is essential when assessing whether extra pay, overtime, or bonuses will meaningfully improve take-home pay.

£80k a Year After Tax UK: Employee vs Employer National Insurance (“The Taxberg” Effect)

Most employees are aware of their own National Insurance deductions because they appear clearly on payslips. What is far less visible — but equally important — is employer National Insurance.

Employer National Insurance explained

In addition to your salary, employers must pay secondary (employer) Class 1 National Insurance on your earnings. For the 2024/25 tax year, the key figures published by GOV.UK are:

- Employer NIC rate: 13.8%

- Secondary Threshold: £9,100 per year

Employer NIC applies to earnings above the secondary threshold and is not deducted from your salary — it is an additional cost borne by the employer.

The real cost of an £80,000 salary to an employer

Using these figures, the employer’s National Insurance bill on an £80,000 salary is approximately:

- Employer NIC ≈ (£80,000 − £9,100) × 13.8%

- Employer NIC ≈ £9,784

This means the true employment cost of a role advertised as “£80,000 salary” is closer to:

- £89,784 per year, before considering:

- employer pension contributions

- benefits-in-kind

- training costs or bonuses

This hidden layer of taxation is often referred to as a “Taxberg” — only part of the cost is visible to the employee, while a significant portion sits below the surface.

Why the “Taxberg” matters in real life

The employer National Insurance cost has practical consequences well beyond payroll calculations. It directly influences:

- salary negotiations, especially at senior levels

- bonus structures, including whether rewards are paid in cash or benefits

- availability of salary sacrifice arrangements, such as pensions or electric vehicle schemes

- decisions around employment vs contractor models

- overall hiring budgets and role design

From a planning perspective, understanding employer NIC helps explain why some employers:

- prefer benefits over straight salary increases

- encourage pension salary sacrifice

- consider limited company or fixed-fee arrangements for certain roles

These dynamics become especially relevant when comparing PAYE employment with alternative working structures, which are explored later in this article.

Official references used in this section (for trust and compliance)

The figures and mechanisms described above are based on official UK government guidance, including:

- Income tax bands and the Personal Allowance — published by GOV.UK

- PAYE tax and National Insurance thresholds, including Class 1 employee and employer rates for 2024/25 — GOV.UK employer rates and thresholds

- National Insurance rates and allowances across tax years — GOV.UK NIC guidance

Using these sources ensures that the calculations and explanations in this section reflect actual payroll rules, not simplified estimates.

Why Your £80k After Tax UK May Be Lower (Pensions, Student Loans, Benefits)

We established a baseline calculation: an employee earning £80,000 per year under PAYE in England, Wales, or Northern Ireland, using tax code 1257L and with no additional deductions, typically takes home around £56,957 in the 2024/25 tax year.

This figure is mathematically correct — but in practice, many people earning £80,000 discover that their actual payslip net pay is lower. This is one of the most common reasons behind searches such as “why is my 80k take home pay lower” or “80k after tax UK calculator wrong”.

The explanation is straightforward: PAYE deductions are not limited to income tax and National Insurance. Payroll can, and often does, deduct other items before your salary reaches your bank account — all legitimately and in line with HMRC rules.

This section explains the most common reasons why your £80k after tax UK figure may be lower than the headline estimate, and why these differences are entirely normal.

The baseline vs real-life payroll

The £56,957 figure represents a clean reference point, not a universal outcome. It assumes:

- no workplace pension contributions

- no student loan repayments

- no taxable benefits

- no household-based tax charges

- no adjustments to your tax code

In reality, many employees at this income level have at least one of these factors in play — and often several at the same time.

Workplace pension contributions

Pension contributions are one of the most common — and most significant — reasons why take-home pay at £80,000 is lower than expected.

Most UK employees are enrolled into a workplace pension under auto-enrolment rules. Even if you have never actively chosen a contribution level, deductions may already be happening.

Key factors that affect how pensions reduce net pay include:

- whether contributions are calculated on qualifying earnings or full salary

- whether the scheme uses a net pay arrangement or relief at source

- whether contributions are made via salary sacrifice

At £80,000, pension contributions often move from being a minor deduction to a material planning tool, and the impact on monthly net pay can range from modest to substantial depending on structure.

Student loan repayments

Student loan repayments are another major reason why an £80k salary may not produce the expected take-home pay.

Unlike income tax and National Insurance, student loan repayments are:

- charged on top of tax

- calculated as a percentage of income above a threshold

- not capped annually

At £80,000, repayments under common plans can reduce take-home pay by around £360–£415 per month, depending on the plan type.

Because these deductions are taken automatically through payroll, many employees underestimate their impact until they see the net figure on their payslip.

Taxable benefits-in-kind

If you receive benefits such as:

- a company car

- private medical insurance

- other employer-provided perks

their taxable value is added to your income for tax purposes. This does not always reduce your salary directly, but it reduces your tax-free allowance or increases taxable pay, which lowers net income.

At higher income levels, even relatively modest benefits can result in noticeable reductions in take-home pay over the year.

High Income Child Benefit Charge (HICBC)

For employees with children, the High Income Child Benefit Charge can significantly affect overall household finances.

Although HICBC is not deducted directly from monthly payslips, it effectively reduces net income through:

- additional tax liabilities

- Self Assessment payments

- PAYE adjustments in some cases

At £80,000, the charge can equal 100% of the Child Benefit received, which can amount to several thousand pounds per year for larger families.

This often explains why household cash flow feels tighter than the headline “after tax” salary suggests.

Tax code adjustments and prior-year corrections

HMRC can adjust your tax code to:

- recover underpaid tax from a previous year

- account for benefits-in-kind

- reflect estimated changes in income

These adjustments are spread across the tax year and reduce monthly take-home pay. Many employees notice these changes only when comparing their payslip to online calculators that assume a standard tax code.

Why these differences matter

Understanding why your £80k after tax UK figure differs from a baseline calculation is essential for:

- accurate budgeting

- assessing the true value of pay rises or bonuses

- planning pension contributions

- deciding whether to seek professional tax advice

At higher income levels, payroll deductions are no longer “background noise” — they are central to how much money you actually have available each month.

Why Your £80k After Tax May Be Lower: Common Deductions

Once you move beyond the baseline calculation, it becomes clear why so many people earning £80,000 a year find that their actual take-home pay is lower than headline “after tax” figures.

At this income level, several additional deductions commonly apply through payroll or the wider tax system. Some reduce your net pay directly each month, while others affect your overall tax position across the year.

This section focuses on the three most common deductions that explain why £80k after tax UK figures vary so widely in practice.

Pension contributions (the number one reason net pay differs)

Workplace pension contributions are the single most common reason why an £80,000 salary does not translate into the expected take-home pay.

Most UK employees are enrolled into a pension scheme under auto-enrolment rules. Even if you have never actively chosen a contribution rate, deductions may already be taking place.

How much your pension reduces your net pay depends on three critical factors.

How pension contributions are calculated

- Qualifying earnings vs total salary

The headline “5% auto-enrolment contribution” is often misunderstood.

In many schemes, the minimum 5% employee contribution is calculated not on your full salary, but on qualifying earnings, which fall within a defined band (between a lower and upper limit set for each tax year).

As a result:

- many employees contribute significantly less than 5% of their full £80,000 salary

- unless they actively choose to increase contributions

Employers are allowed — and often encouraged — to set higher contribution rates, but the statutory minimum is lower than many people assume.

How tax relief is delivered

The way pension tax relief is applied has a direct impact on take-home pay, especially for higher-rate taxpayers.

- A) Net pay arrangement

Under a net pay arrangement:

- pension contributions are deducted from gross salary

- income tax is calculated on the reduced amount

- tax relief is applied automatically through PAYE

For someone earning £80,000, this structure is highly efficient because higher-rate tax relief (40%) is applied immediately, without the need to claim it separately.

This setup is common in many employer schemes and is particularly beneficial for higher earners.

- B) Relief at source

Under relief at source:

- pension contributions are taken from net pay (after tax)

- the pension provider claims basic-rate (20%) tax relief from HMRC

- higher-rate relief is not automatic

If you pay tax at 40%, you usually need to claim the additional 20% relief yourself — often via Self Assessment or by contacting HMRC.

If this extra relief is not claimed, higher-rate taxpayers can unintentionally overpay tax, even though they are contributing to a pension.

Salary sacrifice and National Insurance

Some employers offer pension contributions through salary sacrifice.

In this arrangement:

- your contractual salary is reduced

- pension contributions are made by the employer

- both income tax and employee National Insurance can be reduced

At £80,000, salary sacrifice can materially improve efficiency because it reduces income that would otherwise be subject to 40% tax and National Insurance.

Worked example: 5% pension on £80,000

To illustrate the impact in simple terms:

- Employee contribution: 5% of £80,000 = £4,000 per year (gross)

For a higher-rate taxpayer, if tax relief is handled efficiently:

- the effective reduction in take-home pay can feel closer to £2,400 per year

- because 40% tax relief reduces the “real” cost of the contribution

The exact outcome depends on the pension structure and how higher-rate relief is applied, but this example shows why pensions are not simply a “deduction” — they are also a planning opportunity.

Student loan repayments (particularly significant at £80k)

Student loan repayments are not income tax, but they behave very much like an additional payroll tax.

They are deducted automatically through PAYE and apply on top of income tax and National Insurance.

How student loan repayments work

HMRC applies student loan deductions based on:

- the loan plan you are on

- your income above the relevant threshold

- fixed repayment percentages

The standard rules are:

- 9% of income above the threshold for Plan 1, Plan 2, Plan 4, and Plan 5

- 6% of income above the threshold for a Postgraduate Loan, in addition to any undergraduate loan

2024/25 payroll thresholds

Payroll systems use HMRC’s official deduction tables, which are specific to each tax year.

For 2024/25, the annual thresholds are:

- Plan 1: £24,990

- Plan 2: £27,295

- Plan 4 (Scotland): £31,395

- Postgraduate Loan: £21,000

These thresholds determine how much of your income is subject to the 9% or 6% repayment rates.

Because £80,000 is far above all of these thresholds, repayments at this income level are substantial, often reducing take-home pay by £360–£415 per month, depending on the plan.

Why student loans feel especially heavy at £80k

At higher incomes:

- student loan repayments continue without a cap

- they combine with 40% income tax and National Insurance

- bonuses are often hit particularly hard

This is why many £80k earners experience a large gap between expected and actual net pay, especially in months with variable income.

Benefits-in-kind (BIK): company cars and other perks

Another common reason why £80k take-home pay differs between individuals is the presence of taxable benefits-in-kind.

These benefits do not usually reduce your gross salary, but they increase your taxable income or reduce your Personal Allowance, which lowers net pay.

Common taxable benefits

Examples include:

- company cars

- private medical insurance

- fuel benefits

- other employer-provided perks

A company car is the most frequently encountered example at higher salary levels.

The tax due on a company car depends on:

- the vehicle’s list price

- CO₂ emissions

- fuel type

- your income tax band

Higher-rate taxpayers pay more tax on the same benefit than basic-rate taxpayers.

Why benefits matter for £80k take-home pay UK

Two employees can both earn £80,000, but:

- one may receive only cash salary

- the other may receive taxable benefits alongside salary

As a result, their net pay can differ materially — even though the gross salary figure is identical.

This explains why online calculators often fail to match real payslips unless benefits-in-kind are included correctly.

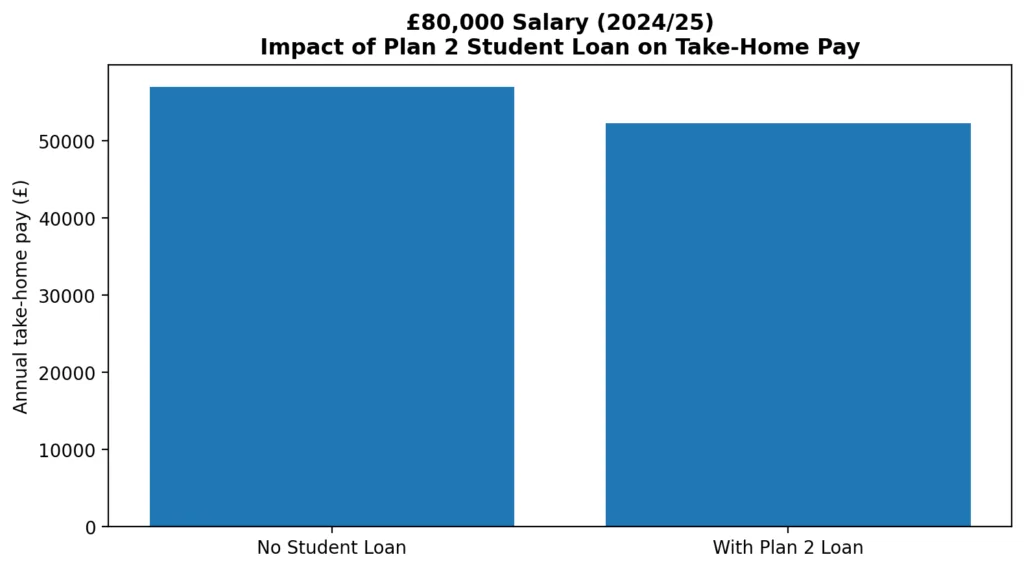

80,000 Salary Take-Home Pay With Student Loan Repayments (Worked Examples)

Below are clean, payroll-style calculations for an £80,000 salary in 2024/25. These show how much the student loan alone can reduce take-home pay.

Table: Student loan deductions at £80,000 salary (2024/25)

Repayment formula (undergrad plans):

Annual repayment = 9% × (Salary − Threshold) if salary is above the threshold.

| Plan | 2024/25 annual threshold | Annual repayment at £80,000 | Monthly equivalent |

| Plan 2 | £27,295 | £4,743.45 | £395.29 |

| Plan 1 | £24,990 | £4,950.90 | £412.58 |

| Plan 4 | £31,395 | £4,374.45 | £364.54 |

| Postgraduate Loan (6%) | £21,000 | £3,540.00 | £295.00 |

Sources: repayment rates and how they’re calculated (9% / 6%) GOV.UK, 2024/25 plan thresholds used by payroll GOV.UK

What does this do to your £80k after tax UK take-home pay?

Take our baseline net pay from Part 1: ~£56,957/year (England/Wales/NI; no deductions).

Now subtract the student loan:

- With Plan 2:

~£56,957 − £4,743 = ~£52,214/year

≈ £4,351/month

Guidance – 2024 to 2025: Student and Postgraduate Loan deduction tables

80k Salary After Tax UK — Student Loan Plan 2 vs Plan 1 (What’s the difference?)

At £80,000:

- Plan 1 takes ~£413/month

- Plan 2 takes ~£395/month

So Plan 1 is slightly higher at this salary, because its threshold in 2024/25 is lower (£24,990 vs £27,295).

But the plan type you’re on depends on where and when you studied — you can’t just “choose” the cheaper plan.

Mini infographic: “£80k salary — net pay vs Plan 2 student loan”

Sources (for the page’s compliance notes): student loan repayment rates (9% / 6%); 2024/25 thresholds

CTA reminder placement note (editorial)

Your CTA block should sit around here (2–3 screen depth), because this is where many readers think:

“Wait — why is my net pay lower than the calculator?”

…and they’re primed to ask for help.

High Income Child Benefit Charge (HICBC) at £80,000: why it can wipe out Child Benefit (and how to plan around it)

If you earn £80,000 a year, the single biggest “unexpected” deduction many UK households face isn’t on the payslip — it’s the High Income Child Benefit Charge (HICBC).

From tax year 2024/25 onwards, the HICBC starts when an individual’s adjusted net income goes over £60,000 (it used to start at £50,000).

And crucially for this page:

- If adjusted net income is £80,000 or more, the charge is 100% of the Child Benefit received (i.e., it can fully cancel out Child Benefit).

- Between £60,000 and £80,000, the charge tapers up gradually at 1% for every £200 of income above £60,000.

That’s why people Googling “80k after tax UK” often feel their finances don’t match the “simple” take-home pay number — Child Benefit can be clawed back separately, and it’s based on adjusted net income, not just salary.

What Exactly Is the High Income Child Benefit Charge (HICBC) and Who Pays It?

The High Income Child Benefit Charge (HICBC) is one of the most misunderstood elements of the UK tax system — and one of the most financially significant for households earning around £80,000 a year.

HICBC is not a reduction in Child Benefit itself, and it does not appear automatically on most payslips. Instead, it is a separate tax charge that applies when:

- Child Benefit is being received by either partner, and

- the partner with the higher adjusted net income exceeds the relevant income threshold

The rules, thresholds, and calculation method are set out in official guidance published by GOV.UK, which also provides a calculator based on adjusted net income, not headline salary.

The key point that catches people out

One of the most common misconceptions about HICBC is who the charge applies to.

It does not matter:

- which partner actually receives the Child Benefit payments

- whose bank account the money goes into

What matters is which partner has the higher adjusted net income.

If one partner’s adjusted net income exceeds the threshold, that person becomes liable for the charge — even if:

- they never claimed Child Benefit themselves

- the benefit is paid to the other partner

This is why HICBC often comes as a shock: the link between the benefit payment and the tax charge is not intuitive, and many households do not realise the charge applies until HMRC issues an assessment.

What this means at £80,000 in practice

At an adjusted net income of £80,000 or above, a common real-world outcome is:

- Child Benefit continues to be paid during the year (cash in)

- A tax charge equal to 100% of the benefit becomes due later (cash out)

Unless this is planned for in advance, it can feel like an unexpected tax bill — even though the rules themselves are clear once understood.

HICBC Rates (2024/25): The £60,000–£80,000 Taper Explained

From the 2024/25 tax year onwards, the HICBC operates using a tapered mechanism between £60,000 and £80,000 of adjusted net income.

The structure is as follows:

- 0% charge if adjusted net income is £60,000 or less

- 1% of Child Benefit is repaid for every £200 of income above £60,000

- 100% charge once adjusted net income reaches £80,000 or more

This taper mechanism is explicitly confirmed in GOV.UK guidance and policy notes.

HICBC taper checkpoints (illustrative)

Adjusted net income and proportion of Child Benefit repaid:

- £60,000 → 0%

- £65,000 → 25%

- £70,000 → 50%

- £75,000 → 75%

- £80,000 and above → 100%

This matches the formal calculation rule of 1% per £200 within the £60k–£80k band, with full repayment above £80k.

How Much Is Child Benefit in 2024/25 — and What Does “100% Repayment” Mean in Pounds?

To understand the financial impact of HICBC, it’s essential to translate percentages into actual cash amounts.

HMRC publishes official weekly Child Benefit rates for each tax year. For 2024/25 (6 April 2024 to 5 April 2025), the rates are:

- £25.60 per week for the eldest or only child

- £16.95 per week for each additional child

Using a 52-week year (sufficiently accurate for planning), the estimated annual amounts are:

- 1 child: £1,331.20

- 2 children: £2,212.60

- 3 children: £3,094.00

These figures align directly with HMRC’s published rates for the year.

What happens at £80,000?

If your adjusted net income is £80,000 or above, the HICBC equals 100% of the Child Benefit received.

In practical terms:

- 1 child → £1,331.20 to repay

- 2 children → £2,212.60 to repay

- 3 children → £3,094.00 to repay

This is why many households at £80,000 feel they are “no better off” receiving Child Benefit — unless:

- they need the National Insurance credits linked to claiming (depending on who claims), or

- they plan to reduce adjusted net income using legitimate planning strategies

“Adjusted Net Income” — The Number HMRC Actually Uses

One of the most important — and least understood — aspects of HICBC is that it is not based purely on gross salary.

HMRC calculates liability using adjusted net income, which is a broader measure that can differ significantly from headline earnings.

GOV.UK provides a step-by-step method for calculating adjusted net income, including how certain deductions reduce it.

What commonly increases adjusted net income?

- Employment income (salary, bonuses)

- Taxable benefits-in-kind (such as company cars or private medical insurance)

- Interest, dividends, and other taxable income

HMRC’s own HICBC calculator explicitly includes taxable benefits when determining adjusted net income.

What can legitimately reduce adjusted net income?

- Certain pension contributions, depending on how they are structured

- Gift Aid donations, grossed up for tax purposes

Where pension contributions are made through a net pay arrangement or salary sacrifice, taxable employment income is already reduced at source — meaning those amounts are effectively reflected automatically in adjusted net income.

This is why pension structure matters so much for households near the HICBC thresholds.

Planning at £80,000: How to Reduce or Eliminate HICBC

Because the HICBC operates on a taper, even small reductions in adjusted net income can have a meaningful effect.

Strategy A — Reduce adjusted net income below £80,000

At exactly £80,000, the charge is 100%.

Reducing adjusted net income even slightly — for example to £79,800 — moves you off the full clawback.

Within the £60k–£80k range:

- every £200 reduction lowers the charge by 1% of Child Benefit

This can quickly translate into hundreds of pounds saved per year.

Strategy B — Reduce adjusted net income below £60,000

This is the cleanest outcome under the rules.

If adjusted net income is £60,000 or less, the HICBC is 0%.

For an £80,000 earner, this broadly requires a £20,000 reduction in adjusted net income. In practice, the most common route is pension planning, particularly where salary sacrifice is available.

Why salary sacrifice can be especially powerful

Where employers offer salary sacrifice:

- taxable pay is reduced

- employee National Insurance may also fall

- adjusted net income is reduced for HICBC purposes

This creates a “triple effect” for some households:

- lower income tax

- lower NICs

- reduced or eliminated HICBC

Where salary sacrifice is not available, pension contributions can still help — but the mechanics differ, and higher-rate relief must be handled correctly.

Worked Planning Illustration: £80,000 Earner With Two Children

Assumptions

- Salary: £80,000

- Children: 2

- Child Benefit (2024/25 estimate): £2,212.60

- Adjusted net income before planning: £80,000

Outcome without planning

- HICBC = 100% × £2,212.60

- Amount to repay: £2,212.60

If adjusted net income is reduced to £70,000

- Income above £60k: £10,000

- £10,000 ÷ £200 = 50

- HICBC = 50% × £2,212.60 ≈ £1,106.30

If adjusted net income is reduced to £60,000

- HICBC = 0%

- No repayment due

This is why advisers often refer to the “Child Benefit trap”: the issue is not just tax — it is household cash flow and avoidable repayments.

Compliance: Do You Need to File a Tax Return Because of HICBC?

In many cases, yes.

If you are liable to HICBC, HMRC generally expects the charge to be:

- reported and paid via Self Assessment, or

- formally accounted for through PAYE adjustments (in specific cases)

Because HICBC amounts at £80,000 can easily run into thousands of pounds, ensuring correct reporting is not optional. HMRC’s HICBC guidance and calculator are the starting point for determining liability — but many households benefit from professional support to ensure everything is handled correctly.

Salary Sacrifice Strategies for £80k Earners

For employees earning £80,000 a year, salary sacrifice is one of the most effective — and most misunderstood — tools available within the UK PAYE system. When structured correctly and offered by the employer, it can materially improve take-home outcomes without breaching HMRC rules.

Salary sacrifice is explicitly recognised by GOV.UK as a legitimate arrangement. Under it, an employee agrees to give up part of their cash salary in exchange for a non-cash benefit. Crucially, the employee’s contractual salary is reduced, meaning the sacrificed amount is no longer treated as pay for tax and National Insurance purposes.

Because of this structural change, salary sacrifice can reduce:

- Income Tax

- Employee National Insurance contributions

- Adjusted net income (which is critical for thresholds such as HICBC)

At £80,000, where higher-rate tax, NICs, and household-level charges often overlap, salary sacrifice can be particularly powerful.

How salary sacrifice differs from “normal” deductions

It is important to distinguish salary sacrifice from deductions taken after salary is earned.

With salary sacrifice:

- your contractual gross salary is reduced

- tax and NICs are calculated on the lower figure

- the sacrificed amount never becomes taxable income

This is why salary sacrifice can be more efficient than simply receiving salary and then paying for the same benefit out of net pay.

Pension Salary Sacrifice — The Gold Standard at £80k

Among all salary sacrifice options, pension salary sacrifice is generally regarded as the most effective for higher-rate taxpayers.

Why pension salary sacrifice works so well at £80,000

At this income level, three separate mechanisms often apply simultaneously:

- income above £50,270 is taxed at 40%

- employee National Insurance continues at 2% above the Upper Earnings Limit

- High Income Child Benefit Charge may apply once adjusted net income exceeds £60,000

Pension salary sacrifice can reduce exposure to all three at once.

Worked illustration: £80,000 salary with £10,000 pension via salary sacrifice

Before salary sacrifice

- Gross contractual salary: £80,000

- Baseline take-home pay (no deductions): ~£56,957

After £10,000 pension salary sacrifice

- New contractual salary: £70,000

- Taxable employment income falls

- Employee National Insurance is calculated on a lower figure

- Adjusted net income falls, reducing or potentially eliminating HICBC exposure

- The pension receives the full £10,000 contribution

The “effective cost” to the employee

Although £10,000 is contributed to the pension, the actual reduction in take-home pay is far smaller.

This is because:

- income tax at 40% is avoided on the sacrificed amount

- employee National Insurance is also avoided

- in some cases, employers share part of their NIC savings

As a result, the out-of-pocket impact can feel significantly less than £10,000, while the full amount is invested for the employee’s future.

This efficiency is why pension planning is usually the first topic accountants raise with £80k earners — particularly for families affected by Child Benefit tapering.

HMRC confirms that pension contributions made via salary sacrifice reduce taxable pay because the sacrificed amount is no longer treated as salary.

Practical considerations and limitations

- Salary sacrifice is employer-led — not all employers offer it

- Changes usually require a formal contract variation

- It may affect reference pay for certain statutory benefits

- Annual allowance and long-term pension planning still matter

Despite these considerations, where available, pension salary sacrifice is often the most impactful single planning tool at this income level.

Electric Vehicle (EV) Salary Sacrifice Schemes

Another increasingly popular salary sacrifice option for higher earners is an electric vehicle (EV) company car scheme.

While company cars were historically tax-inefficient, this has changed dramatically for electric vehicles.

Why EV salary sacrifice schemes appeal to £80k earners

EV schemes can be attractive because:

- Benefit-in-Kind (BIK) rates for electric vehicles are significantly lower than for petrol or diesel cars

- the cost is taken from gross salary under a salary sacrifice arrangement

- taxable income and adjusted net income may be reduced

- access to a new vehicle is combined with predictable monthly costs

HMRC publishes official BIK rates by fuel type and CO₂ emissions and confirms the preferential treatment of electric vehicles under the current system.

How EV salary sacrifice interacts with tax at £80k

For a higher-rate taxpayer:

- a low BIK percentage means relatively little additional income tax

- salary sacrifice reduces taxable pay before tax is calculated

- the structure can be more efficient than leasing privately from net income

This makes EV salary sacrifice particularly appealing for employees who were already considering changing vehicles.

Important editorial and practical notes

EV salary sacrifice schemes are highly employer-specific.

Their effectiveness depends on:

- the leasing rates negotiated by the employer

- how employer National Insurance savings are treated

- mileage needs and vehicle choice

- individual tax position and benefits mix

Because of these variables, EV schemes are not universally beneficial — but when structured well, they can be a tax-efficient alternative to private car ownership for £80k earners.

Avoiding the High Income Child Benefit Charge (HICBC) at £80k

Earlier in this guide, we explained why the High Income Child Benefit Charge (HICBC) becomes such a significant issue at an £80,000 salary. At this level of income, the charge can fully eliminate the value of Child Benefit, often catching households by surprise.

This section focuses on the practical question most families ask next:

“What can we actually do about it?”

The key planning principle behind HICBC

The most important concept to understand is this:

HICBC is based on adjusted net income, not your headline salary.

This distinction is critical. HMRC does not look only at the number on your employment contract. Instead, it looks at a broader income measure that can be legitimately reduced through certain types of planning.

If you can reduce adjusted net income:

- below £80,000, you move off the 100% repayment cliff

- below £60,000, the HICBC disappears entirely

Both the thresholds and the taper mechanism are clearly confirmed in guidance published by GOV.UK.

This is why HICBC is often described as a planning issue, not just a tax issue.

Pension Contributions as a Child Benefit Planning Tool

Among all available planning options, pension contributions are one of the most powerful — and explicitly recognised — ways of reducing adjusted net income.

HMRC guidance confirms that qualifying pension contributions can reduce adjusted net income for the purposes of HICBC calculations, provided they are structured and reported correctly.

Why £80k earners are a “sweet spot” for pension planning

Households earning around £80,000 sit in a unique position where pension planning is unusually effective.

First, income above £50,270 is taxed at 40%, meaning pension contributions attract higher-rate tax relief.

Second, £80,000 lies at the top of the HICBC taper, where even small reductions in adjusted net income can produce disproportionately large savings in Child Benefit repayments.

Third, most people earning £80,000 are still many years away from retirement, allowing pension contributions to benefit from long-term compounding rather than acting merely as short-term tax mitigation.

This combination makes pension planning exceptionally powerful for families affected by HICBC.

Why structure matters

Not all pension contributions reduce adjusted net income in the same way.

The impact depends on:

- whether contributions are made via salary sacrifice

- whether the scheme uses a net pay arrangement or relief at source

- whether higher-rate relief is claimed correctly

This is why two families with identical salaries and children can experience very different HICBC outcomes — even when both are “paying into a pension”.

Claiming Child Benefit vs Opting Out

When families first become aware of HICBC, a common reaction is to consider stopping Child Benefit payments altogether to avoid future tax complications.

While this may seem like a simple solution, it is not always the most appropriate one.

Why opting out is not always ideal

According to GOV.UK guidance, claiming Child Benefit can be important because it may protect National Insurance credits, particularly for:

- a non-working partner

- a lower-earning partner

- someone caring for children and not building NI credits through employment

These credits can count towards future State Pension entitlement, which means the long-term impact of opting out can extend far beyond the immediate tax year.

The approach many advisers recommend

For this reason, many advisers suggest a more nuanced approach:

- continue to claim Child Benefit, but

- manage adjusted net income through legitimate planning, where possible

This keeps National Insurance records protected while reducing — or even eliminating — the HICBC liability.

Why joined-up advice matters at £80k

HICBC sits at the intersection of:

- personal tax

- household income planning

- pension strategy

- PAYE and Self Assessment compliance

Generic calculators often fail to capture this interaction properly. That is why households earning around £80,000 frequently benefit from joined-up advice, rather than treating Child Benefit, pensions, and PAYE deductions as separate issues.

£80k Take-Home Pay: PAYE vs Limited Company (Contractors & Consultants)

A recurring question from higher earners — particularly consultants, IT specialists, project managers, and other in-demand professionals — is:

“Would I take home more if I operated through a limited company instead of PAYE?”

The honest answer is:

Sometimes — but not always.

And the “sometimes” depends on a combination of factors that matter far more than the headline day rate or annual figure. Structure can improve net income in certain scenarios, but in others it can create compliance risk, reduce certainty, and add admin without delivering a meaningful benefit.

PAYE employee at £80k (recap)

To compare fairly, we need a clear PAYE baseline.

For a standard employee in England/Wales/Northern Ireland under PAYE in 2024/25 (tax code 1257L, no additional deductions):

- Gross salary: £80,000

- Estimated take-home pay: ~£56,957 per year

- Monthly take-home pay: ~£4,746

This is what most people mean when they search “80k after tax UK” — a straightforward PAYE position.

The part many people forget: employer cost is higher than salary

Employees see only their own income tax and National Insurance deductions. Employers, however, also pay employer National Insurance (and often pension contributions), which increases the total cost of hiring.

At £80,000, once you add employer National Insurance (and before pension or benefits), the employer’s true cost is typically close to £90,000.

This “hidden cost” is one reason businesses are sometimes open to contractor arrangements — because their budgeting is often based on total employment cost, not salary alone.

However, moving from employment to contracting is not a simple “swap”. In the UK, it is constrained by the IR35 / off-payroll working rules, which determine whether someone can legitimately be treated as a contractor rather than an employee in substance.

Limited company contractor: why the numbers can differ

A limited company (often called a “personal service company”) allows earnings to be received by the company, and then extracted by the director/shareholder in multiple ways.

The common extraction tools are:

- a small salary (often set around thresholds for tax/NIC planning)

- dividends, paid from post-tax profits

- company pension contributions (employer pension contributions made by the company)

The UK tax system treats salary and dividends differently, and it treats company pension contributions differently again — and that is where the potential advantage can come from.

HMRC provides rules and guidance on dividends, company tax, and director remuneration, and these rules must be followed precisely.

Why some £80k-equivalent contractors can see higher net pay

In broad terms, a limited company can sometimes improve net pay because:

1) Corporation tax can be lower than higher-rate income tax on part of profits

Profits in a company are taxed under corporation tax rules, which can be lower than paying 40% income tax on equivalent salary. The difference is not always dramatic, but it can be meaningful depending on profit level and extraction strategy.

2) Dividends are taxed differently from salary

Dividends do not attract employee National Insurance and are taxed under dividend tax rates (after any available allowances). This often changes the overall tax/NIC mix compared with PAYE salary.

3) Company pension contributions can be highly efficient

Pension contributions made directly by the company are generally deductible for corporation tax purposes and do not attract National Insurance in the way salary does. This can be particularly attractive for higher earners who are already planning to invest for the long term.

These mechanisms explain why some contractors operating outside IR35 can increase net income compared with an equivalent PAYE salary — especially if they manage their extraction strategy carefully and keep compliance strong.

Why it’s not automatic — and can be a bad idea in the wrong case

It is equally important to understand why a limited company structure is not a guaranteed win.

1) IR35 / off-payroll rules may apply

If your contract is “inside IR35”, then much of the tax treatment begins to resemble employment. In many cases, the net benefit of operating via a limited company drops sharply, and the compliance burden remains.

2) Limited companies have additional compliance costs and admin

Running a company typically involves:

- bookkeeping and record-keeping

- annual accounts

- corporation tax returns

- payroll filings (even if only for a small salary)

- dividend paperwork and board minutes

- potentially VAT returns

- Self Assessment for the director

These costs and responsibilities must be factored into the decision. If the net uplift is small, the structure may not be worth the complexity.

3) Cash flow and risk profile are different

PAYE employees typically have:

- predictable monthly income

- employer benefits (holiday pay, sick pay, pension contributions)

- lower administrative responsibility

Contractors often have:

- gaps between contracts

- greater income volatility

- responsibility for taxes and planning

- higher personal risk exposure

A structure that looks “tax efficient” on paper may be less attractive once uncertainty and risk are priced in.

This is why responsible advisers never promise a fixed net uplift such as:

“You’ll definitely be £5,000 better off.”

Instead, they model scenarios properly and consider both tax and commercial reality.

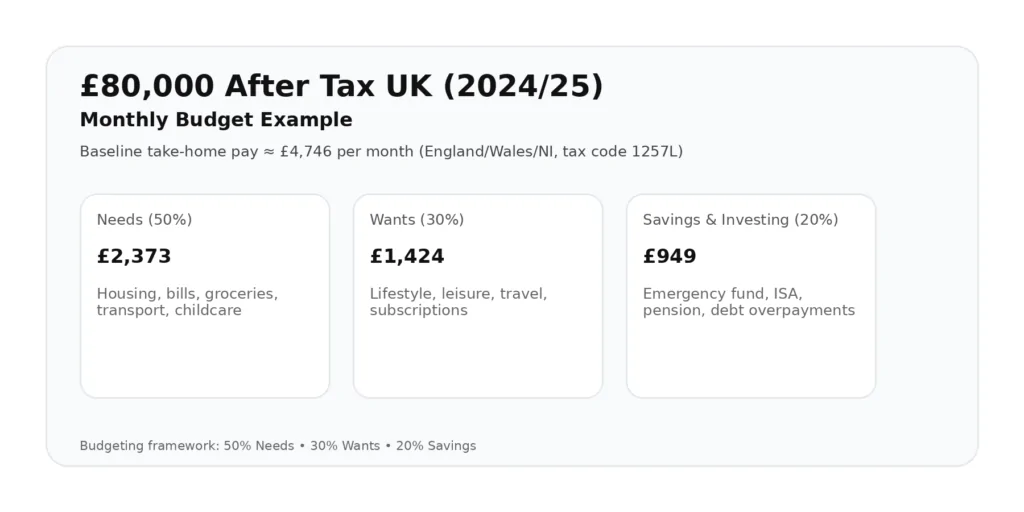

Budget Allocation: The 50/30/20 Rule on £80k Take-Home Pay

Once you understand your £80k take-home pay UK figure, the next practical question is not about tax anymore — it’s about how that money actually works in day-to-day life.

A common mistake among higher earners is to focus heavily on gross salary, while underestimating how quickly money can be absorbed by lifestyle costs, housing, and commitments. That’s why many people benefit from a simple, structured budgeting framework that translates net pay into clear spending categories.

One of the most widely used frameworks is the 50/30/20 rule.

What is the 50/30/20 rule?

The 50/30/20 rule is a rule of thumb, not a rigid prescription. It divides your net monthly income into three broad categories:

- 50% Needs

Essential living costs such as housing, utilities, food, transport, insurance, and childcare. - 30% Wants

Discretionary spending such as eating out, travel, hobbies, entertainment, subscriptions, and non-essential shopping. - 20% Savings / Investing

Building long-term financial resilience through emergency funds, ISAs, pension top-ups, and debt overpayments.

The rule is not UK-specific, but it is popular because it is:

- easy to understand

- flexible

- adaptable to different income levels and locations

For higher earners, it provides a useful reality check: earning more does not automatically mean financial security unless savings scale with income.

Applying the 50/30/20 Rule to an £80,000 Salary (After Tax)

Using the baseline take-home pay established earlier in this guide:

- Annual net pay: ~£56,957

- Monthly net pay: ~£4,746

The 50/30/20 framework translates into the following monthly budget.

Table: 50/30/20 Budget on £4,746 Monthly Net Pay

Needs (50%)

- £2,373 per month

- Covers:

- rent or mortgage payments

- council tax and utilities

- groceries

- commuting and transport

- insurance

- childcare and other unavoidable costs

Wants (30%)

- £1,424 per month

- Covers:

- dining out and takeaways

- holidays and travel

- leisure activities and hobbies

- subscriptions and memberships

- discretionary shopping

Savings / Investing (20%)

- £949 per month

- Covers:

- emergency fund contributions

- Stocks & Shares ISA or Cash ISA

- pension top-ups

- overpayments on mortgages or other debt

These figures are rounded and align with the benchmarks specified in your brief. They are intentionally realistic rather than aspirational — the goal is usability, not perfection.

This kind of “Saving Tool–style” budgeting helps readers move from abstract tax numbers to practical financial planning.

How the Budget Changes With a Plan 2 Student Loan

As shown earlier in the article, student loan repayments can materially change monthly cash flow.

At an £80,000 salary in 2024/25, a Plan 2 student loan typically costs:

- ~£4,743 per year

- ~£395 per month

Applying this deduction to the baseline net pay:

- Original net pay: £4,746 per month

- Less student loan: ~£395

- Revised net pay: ~£4,351 per month

Using the same 50/30/20 framework, the budget adjusts as follows.

Table: 50/30/20 Budget on £4,351 Monthly Net Pay (With Plan 2 Loan)

Needs (50%)

- £2,176 per month

Wants (30%)

- £1,305 per month

Savings / Investing (20%)

- £870 per month

Why this matters for “£80k after tax UK” expectations

This comparison highlights a key reality for many higher earners:

- headline “after tax” figures often ignore student loans

- student loans reduce usable income every single month

- the impact is ongoing and uncapped

This is why two people on the same £80,000 salary can experience very different lifestyles and saving capacity, even before considering housing costs or location.

It also explains why many people feel that an £80k salary does not stretch as far as expected — not because the salary is low, but because additional deductions materially change cash flow.

Flexibility and realism

The 50/30/20 rule is not a moral standard. In real UK life:

- London housing costs may push “Needs” above 50%

- parents may prioritise savings over wants

- aggressive mortgage overpayments may temporarily exceed 20% savings

What matters is not strict adherence, but conscious allocation — knowing where your money is going, and why.

Mini infographic placement (editorial note)

Mortgage Affordability on £80,000 (UK Context)

Once people understand their £80k take-home pay UK figure and how monthly cash flow works, the next major question is usually about property:

“How much can I realistically borrow on an £80,000 salary?”

In the UK, mortgage affordability is assessed using a combination of income multiples and detailed affordability checks. While lenders increasingly focus on net income and outgoings, income multiples remain a useful starting point for planning.

The UK rule-of-thumb: income multiples

A commonly used rule-of-thumb in the UK mortgage market is that lenders may offer around 4.5 times annual salary for a single applicant.

This multiple is not fixed and can vary depending on:

- credit history and credit score

- existing financial commitments

- childcare and dependent costs

- whether the application is sole or joint

- interest rate environment

- lender-specific affordability and stress testing models

Some lenders may offer lower multiples (around 4.0×), while others may stretch to 5.0× or more for applicants with strong profiles and low outgoings.

Illustrative borrowing power on an £80,000 salary

The table below shows how borrowing capacity can vary depending on the income multiple applied.

Salary | Multiple | Illustrative maximum loan

£80,000 | 4.0× | £320,000

£80,000 | 4.5× | £360,000

£80,000 | 5.0× | £400,000

These figures are illustrative, not guarantees. They are designed to frame expectations rather than predict individual lender decisions.

Why take-home pay matters more than salary alone

While income multiples provide a headline number, modern mortgage affordability is heavily influenced by net monthly income and committed outgoings.

At £80,000, factors that can materially reduce borrowing capacity include:

- student loan repayments, which reduce monthly disposable income

- childcare costs, especially nursery fees

- high ongoing commitments such as car finance or personal loans

- credit card balances or other unsecured debt

For example, an £80k earner with:

- a Plan 2 student loan

- childcare costs

- and high fixed monthly expenses

may be offered a significantly lower loan than another £80k earner with minimal outgoings — even though their gross salary is identical.

This is why lenders increasingly stress-test affordability against net pay after deductions, not just headline salary.

Sole vs joint applications

Mortgage affordability also changes materially depending on whether the application is:

- sole, based on one income

- joint, combining two incomes

A joint application can increase borrowing capacity, but it also introduces:

- joint liability

- combined credit profiles

- shared affordability constraints

In some cases, a second income can lift borrowing power substantially. In others — particularly where the second applicant has high outgoings or weaker credit — the uplift may be more modest than expected.

Interest rates and lender stress tests

Lenders do not assess affordability based solely on the current mortgage rate. Instead, they apply stress tests, modelling whether the borrower could still afford repayments if rates were higher.

As interest rates rise:

- stress tests become stricter

- borrowing multiples may compress

- affordability caps can tighten

This means that the same £80,000 salary may support different borrowing amounts in different interest rate environments.

Responsible framing for this page

To keep guidance accurate and compliant, it’s important to position mortgage figures correctly.

The right message for an £80k salary is:

- income multiples provide a useful planning range

- real affordability depends on net pay and commitments

- individual outcomes vary by lender and personal circumstances

Presenting borrowing power as a starting point rather than a promise helps readers set realistic expectations and avoids the frustration that comes from relying on overly optimistic figures.

£80k Salary After Taxes: Living in London vs Regional UK

Two people can earn the same £80,000 salary and have very similar “after tax” figures — yet experience completely different lifestyles depending on where they live.

This is one of the biggest reasons higher earners sometimes feel confused by online discussions around “80k after tax UK”. The tax calculation may be broadly consistent, but the cost-of-living reality is not.

Starting point: the baseline net pay benchmark

Using the baseline PAYE scenario for England/Wales/Northern Ireland in 2024/25:

- Monthly take-home pay: ~£4,746

That figure looks strong on paper. The key question is how much of it is consumed by non-negotiable costs (housing, bills, childcare, commuting). These “needs” determine whether £80k feels like:

- a comfortable middle-class lifestyle, or

- a high-stress income that still leaves little room for saving

Why London can feel “tighter” even on £80k

London is often the first place where higher earners notice that salary and lifestyle are not directly proportional. Even with a strong net pay figure, costs can absorb income quickly.

London (and parts of the South East) typically involves:

- higher rents and housing costs (often the single biggest pressure point)

- higher childcare costs, especially for nursery-age children

- higher commuting costs, particularly if you travel daily and do not live centrally

- higher “baseline” spending, including food, services, and everyday convenience costs

- social pressure to spend, such as networking, events, dining out, and professional lifestyle expectations

This combination means that even on £4,746 per month net, the “needs” category can exceed the 50/30/20 guideline.

This matters because savings are rarely what people intend to compromise first. In many households, the squeeze shows up as:

- reduced saving and investing

- delayed deposit building

- less pension planning capacity

- reliance on bonuses for financial progress

Scenario A: London renter (illustrative budget pressure)

A typical London example is someone renting a one- or two-bedroom property and paying for utilities and council tax.

If rent + bills land around £2,400–£3,200 per month (depending on area, transport zones, and household size), that single expense can absorb:

- 51% to 67% of a £4,746 net monthly income

In other words, housing alone can consume all of the “needs” budget under a 50/30/20 plan before groceries, transport, or childcare are even included.

This is why many £80k earners in London say:

- “I earn a lot, but I don’t feel like I’m saving enough.”

- “My salary looks high, but it disappears.”

At this point, household planning becomes less about “how much do I earn?” and more about:

- “How much is fixed each month?”

- “How exposed am I to rent increases?”

- “Can I reduce commitments through lifestyle design or tax-efficient planning?”

What typically breaks the 50/30/20 rule in London?

Even disciplined households can struggle to keep needs at 50% because London costs are concentrated in categories that are hard to reduce quickly:

- rent / mortgage

- childcare

- commuting

- council tax and utilities

When these rise, households usually do one of three things:

- reduce savings

- reduce discretionary spending significantly

- change housing location or household structure

That’s why many London households treat the 50/30/20 rule as an aspiration rather than a realistic baseline.

Why £80k can feel “upper-middle” outside London

Outside London and the most expensive parts of the South East, the same £80,000 salary often feels materially different — primarily because housing costs are lower relative to income.

In many UK regions and cities, lower housing costs can mean:

- more disposable income

- easier saving and investing

- faster deposit building

- greater capacity to make pension contributions strategically

- ability to absorb shocks (car repairs, childcare changes, interest rate rises) without breaking the budget

This is why £80k can feel more like an “upper-middle” lifestyle in regional areas: not because spending is low, but because core fixed costs take a smaller share of income.

Scenario B: Regional homeowner (illustrative stability)

In many regions, it is more realistic for an £80k earner (or household) to have mortgage + bills closer to:

- £1,400–£1,900 per month

If we compare that to the same £4,746 net pay:

- £1,400 is ~29% of net pay

- £1,900 is ~40% of net pay

This is typically within (or closer to) the 50% “needs” range, leaving space for:

- a consistent 20%+ savings rate

- meaningful ISA contributions

- mortgage overpayments

- pension top-ups (especially valuable at higher-rate tax levels)

In other words, regional affordability often makes financial progress feel more controllable and less dependent on bonuses or salary jumps.

Building a UK Plan on £80k a Year After Tax

Once you know your £80k take-home pay UK figure, the next step is turning it into a plan you can actually follow. At this income level, the biggest risk is not “earning too little” — it is earning well but letting money leak through predictable gaps: unmanaged cash flow, expensive debt, inefficient savings, and missed tax planning opportunities.

Below is a practical, accountant-style framework that many higher-rate PAYE earners use. It is designed to be realistic, not idealistic — and it works whether you live in London, the South East, or elsewhere in the UK.

This plan is not personalised financial advice. It is a structured approach that helps you prioritise the fundamentals and avoid the most common mistakes higher earners make.

Step 1 — Stabilise cash flow (build a 3–6 month emergency fund)

Before investing aggressively or making long-term commitments, the first priority is stabilising cash flow. At £80,000, income is strong — but household obligations can still create vulnerability, especially if you have:

- childcare costs

- a mortgage or high rent

- car finance

- student loan deductions

- variable bonus income

An emergency fund protects you against predictable disruptions such as:

- job changes or contract gaps

- unexpected bills (repairs, medical costs, family emergencies)

- interest rate increases

- short-term income shocks (bonus structure changes, overtime reductions)