The End of Anonymity in UK Business

How the Transformation of Companies House Is Redefining Corporate Transparency from 18 November 2025

A data-driven investigative report based on official UK government sources, statutory reforms, and regulatory impact analysis

Introduction

Why the UK Corporate Register Became a National Risk — and Why the State Finally Acted

For decades, the United Kingdom has been regarded as one of the easiest and fastest jurisdictions in the world in which to incorporate a company. The simplicity of the process, the low cost, and the absence of substantive identity checks helped position the UK as a global business hub.

However, the same features that made incorporation efficient also created a structural vulnerability at the heart of the UK corporate system.

The public register of companies — maintained by Companies House — gradually evolved into something it was never designed to be:

a vast repository of unverified identities, unconfirmed corporate control, and data that could be submitted without meaningful scrutiny.

By the early 2020s, this vulnerability was no longer theoretical.

Official government reviews, parliamentary debates, and law-enforcement assessments increasingly pointed to the same conclusion:

the UK company register was being systematically exploited — not only by fraudsters, but by organised crime networks, money launderers, and professional enablers operating at scale.

Companies were incorporated using:

- fictitious directors,

- stolen or fabricated identities,

- implausible residential addresses,

- nominee structures with no effective accountability,

- and corporate control chains that could not be meaningfully traced.

In many cases, these companies existed solely on paper — yet they were able to:

- open bank accounts,

- enter contracts,

- trade internationally,

- and lend an appearance of legitimacy to illicit financial flows.

– It could register information, but not verify it.

– It could publish filings, but not question their plausibility.

– It could record directors, but not confirm that they were real people.

This systemic weakness became increasingly incompatible with the UK’s broader commitments to combat economic crime, improve corporate transparency, and maintain international credibility as a trusted place to do business.

The result was inevitable.

In 2023, the UK Parliament passed the Economic Crime and Corporate Transparency Act, initiating the most radical reform of Companies House since its creation. The reform fundamentally alters the role of the registrar — transforming it from a passive filing office into an active gatekeeper of corporate data.

At the centre of this transformation lies one change that will affect almost every UK company without exception:

mandatory identity verification for directors and persons with significant control, beginning its phased rollout on 18 November 2025.

This article is not a summary of legislative headlines.

It is a forensic examination of how and why the UK corporate register failed, what the government’s own data reveals about the scale of the problem, and how the new regulatory architecture will reshape corporate compliance, governance, and risk for UK businesses over the next decade.

Drawing exclusively on:

- official UK government publications,

- statutory guidance,

- regulatory impact assessments,

- and Companies House reform documentation,

we analyse not only what is changing, but what the data suggests will happen next — and which businesses are most exposed if they fail to adapt.

Scope of This Investigation

This report will examine:

- why Companies House was historically unable to prevent misuse of the UK company register;

- the legal and operational consequences of the Economic Crime and Corporate Transparency Act;

- how identity verification will work in practice for directors, PSCs, and agents;

- what official data reveals about corporate misuse prior to reform;

- the new powers granted to the registrar — and how they will be exercised;

- and how legitimate businesses can prepare for a regulatory environment that is no longer tolerant of ambiguity.

Where appropriate, we will support our analysis with:

- timelines of statutory implementation,

- comparative “before and after” regulatory frameworks,

- process flow diagrams,

- and data-driven visualisations derived from official sources.

Why This Matters to Legitimate Businesses

For legitimate UK companies — particularly owner-managed businesses, international groups, and structures involving nominees or corporate shareholders — the reform introduces new compliance obligations, new failure points, and new expectations of data accuracy.

In a system that now prioritises verification over convenience, good faith is no longer sufficient.

Accuracy, traceability, and proactive compliance will become defining features of sustainable corporate operations in the UK.

From Passive Registrar to Systemic Weakness

How the Historical Design of Companies House Enabled Abuse

To understand the scale and significance of the current reform, it is necessary to examine how the UK corporate register was historically constructed — and, more importantly, what it was never designed to do.

Companies House was created as an administrative body, not a regulatory authority. Its original mandate was narrow and procedural: to receive, record, and publish information submitted by companies. The underlying assumption was simple and largely unquestioned for decades — that the information provided by company officers was submitted in good faith and could therefore be relied upon.

This assumption shaped every aspect of the system.

Directors could be appointed without proving their identity.

Persons with Significant Control (PSCs) could be declared without independent verification.

Addresses could be listed with minimal scrutiny.

Corporate filings were accepted unless they were incomplete or incorrectly formatted — not because they were implausible.

The registrar’s role was intentionally passive.

By design, Companies House had:

- no obligation to verify the accuracy of submitted data,

- no authority to demand corroborating evidence,

- no power to reject filings on the basis of suspicion,

- and no responsibility for assessing whether information was misleading, fictitious, or fraudulent.

In effect, the UK corporate register functioned as a self-reporting database, where compliance was procedural rather than substantive.

Speed Over Scrutiny: A Structural Trade-Off

The UK prided itself on being one of the fastest incorporation jurisdictions globally. A company could be formed in a matter of hours, at negligible cost, and without face-to-face interaction or identity checks.

This efficiency was not accidental — it was the result of deliberate policy choices.

However, speed came at a price.

As digital filing expanded and incorporation volumes increased, the absence of verification mechanisms meant that scale amplified vulnerability. The system worked tolerably well when abuse was limited. It became untenable once abuse became industrialised.

Government-commissioned reviews later acknowledged that the very features marketed as advantages — low barriers, minimal friction, rapid processing — had become vectors of exploitation.

When Data Quality Became a National Concern

Law enforcement agencies, financial institutions, and international partners began flagging the UK register as a recurring point of entry in complex financial crime cases.

Official assessments highlighted recurring patterns:

- directors listed with obviously false names,

- thousands of companies registered to single residential addresses,

- implausible dates of birth (including minors and centenarians),

- and PSC declarations that obscured rather than clarified control.

Crucially, these were not isolated anomalies.

They reflected a deeper structural issue: Companies House could not distinguish between legitimate filings and abusive ones — because it was never empowered to do so.

The registrar was legally obliged to accept information that met formal requirements, even where that information was internally inconsistent or plainly unlikely.

The Illusion of Transparency

Paradoxically, the UK company register was often cited as an example of transparency — because it was public.

Yet transparency without verification is fragile.

Public availability does not guarantee reliability. In fact, unverified openness can create a false sense of security, particularly for third parties who rely on the register to:

- conduct due diligence,

- assess counterparties,

- or comply with anti-money laundering obligations.

Banks, investors, and professional advisers increasingly found themselves in a contradictory position:

legally required to rely on a register that the state itself acknowledged was not designed to be accurate.

This tension became unsustainable.

International Pressure and Reputational Risk

The UK’s approach to corporate registration did not exist in isolation.

International bodies focused on financial integrity repeatedly emphasised the importance of beneficial ownership transparency and identity verification as core components of effective anti–economic crime frameworks.

Comparative assessments highlighted a growing gap between:

- the UK’s stated commitments to transparency, and

- the practical limitations of its corporate registry.

As global scrutiny intensified, the risk was no longer merely domestic fraud — it was reputational erosion.

A register that could be easily manipulated undermined:

- trust in UK corporate data,

- confidence in UK-incorporated entities abroad,

- and the credibility of the UK as a leader in corporate governance standards.

Why Incremental Fixes Were No Longer Enough

For years, reform efforts focused on mitigation rather than transformation.

Guidance was updated.

Filing requirements were expanded.

New disclosure concepts, such as PSCs, were introduced.

Yet each of these measures relied on the same flawed premise:

that companies would accurately self-report without independent verification.

The evidence increasingly suggested otherwise.

By the early 2020s, the government’s own documentation acknowledged that only a structural redesign of Companies House could address the problem.

That redesign required:

- redefining the registrar’s purpose,

- expanding its legal authority,

- and introducing identity-based accountability at the point of entry into the corporate system.

This acknowledgement marked a turning point.

Setting the Stage for Radical Reform

The Economic Crime and Corporate Transparency Act did not emerge in a vacuum. It was the culmination of:

- years of data indicating systemic misuse,

- mounting pressure from enforcement agencies,

- and recognition that the UK’s corporate infrastructure was being used in ways fundamentally incompatible with modern economic crime risks.

Most importantly, it represented a philosophical shift:

From a system built on trust by default,

to one grounded in verification by design.

The next section examines how this shift was codified into law — and what exactly the Economic Crime and Corporate Transparency Act changed at a statutory level.

The Economic Crime and Corporate Transparency Act

What the Law Actually Changed — and Why It Redefined the Registrar’s Role

Rather than treating Companies House as a neutral repository of information, Parliament explicitly redefined it as an active participant in the prevention of economic crime.

This shift is not symbolic. It is embedded directly in statute.

The Act rewrites the registrar’s objectives, powers, and obligations — and, in doing so, fundamentally alters the compliance landscape for every UK company.

A New Statutory Objective: Data Integrity, Not Mere Disclosure

At the heart of the reform lies a redefinition of purpose.

Historically, the registrar’s primary function was administrative: to ensure that information was delivered in the correct form and made publicly available. Under the ECCT Act, that logic is reversed.

The registrar is now required to:

- promote the integrity and accuracy of the information on the register,

- ensure that the register is not used for unlawful purposes,

- and actively minimise the risk of economic crime facilitated through corporate structures.

This is a critical distinction.

The register is no longer neutral with respect to content. Accuracy is no longer assumed; it is a regulatory objective.

Expanded Powers to Question, Reject, and Remove Information

To support this new objective, the Act grants the registrar powers that were previously absent or severely limited.

These include the authority to:

- query information that appears inconsistent, misleading, or suspicious,

- require additional evidence before accepting filings,

- reject documents that do not meet substantive standards,

- and remove or annotate information already on the register if it is found to be incorrect or fraudulent.

This represents a sharp break from the earlier “accept unless incomplete” model.

Importantly, these powers apply not only to new incorporations, but also to existing companies and historical data.

Identity as a Legal Gatekeeping Mechanism

Perhaps the most consequential innovation introduced by the ECCT Act is the legal requirement for identity verification.

For the first time, UK company law explicitly recognises that:

- control over a company must be traceable to a real, verified individual,

- and that anonymity is incompatible with corporate legitimacy.

The Act establishes identity verification as a precondition for participation in corporate governance, rather than a post hoc compliance exercise.

Directors and persons with significant control are no longer simply named — they must be verified.

This distinction underpins the entire reform architecture.

Regulating the Intermediaries: Authorised Corporate Service Providers

Another structural weakness addressed by the Act concerns intermediaries.

For years, company formation agents and service providers played a central role in incorporating and managing UK companies — often acting as buffers between the state and the ultimate controllers of corporate entities.

The ECCT Act introduces a new regulatory concept: Authorised Corporate Service Providers (ACSPs).

Under this framework:

- only authorised agents will be permitted to submit filings on behalf of companies,

- agents will be required to verify identities and retain evidence,

- and the registrar will be able to suspend or revoke authorisation where standards are breached.

This has two profound implications.

First, responsibility for compliance is no longer diffused.

Second, professional enablers become subject to direct regulatory oversight, rather than operating in a grey zone between company law and AML regulation.

The Lawful Purpose Statement: A Quiet but Powerful Requirement

One of the less publicly discussed provisions of the Act is the introduction of a lawful purpose statement.

Companies are now required to affirm that they are being formed and operated for lawful purposes. While this may appear declaratory, its legal significance should not be underestimated.

By embedding this requirement into the incorporation process, the Act:

- creates a formal representation that can be relied upon by regulators,

- provides a basis for enforcement where misuse is later identified,

- and reinforces the principle that corporate status is conditional, not automatic.

This aligns company law more closely with regulatory regimes that treat authorisation as contingent on ongoing compliance.

Registered Office and Contactability: Ending the Fiction of “Paper Presence”

The Act also tightens the concept of a registered office.

Under the new framework, a registered office must be:

- appropriate,

- capable of receiving official correspondence,

- and demonstrably linked to the company’s administrative reality.

This change responds directly to widespread abuse involving:

- mass-registered addresses,

- locations with no meaningful connection to the company,

- and premises used to obscure accountability.

In addition, companies must provide a registered email address, reinforcing the expectation that corporate entities are reachable and responsive.

Enforcement by Design, Not Afterthought

A defining feature of the ECCT Act is its emphasis on front-loaded enforcement.

Rather than relying primarily on penalties after misconduct occurs, the Act focuses on:

- preventing misuse at the point of entry,

- limiting the ability to create opaque structures,

- and enabling early intervention.

This reflects a broader regulatory trend: moving from reactive enforcement to systemic prevention.

Why This Legal Shift Matters in Practice

For businesses, the implications are far-reaching.

Company law in the UK is no longer purely facilitative. It is conditional.

Access to the corporate form now depends on:

- verified identity,

- accurate disclosure,

- lawful intent,

- and ongoing compliance with data integrity requirements.

For companies accustomed to minimal scrutiny, this represents a cultural and operational shift.

For those already operating transparently, it creates new obligations — but also a more trustworthy environment in which to operate.

Laying the Groundwork for Identity Verification

While the ECCT Act establishes the legal foundation, its most visible impact will be felt through its implementation — particularly the phased rollout of identity verification beginning in November 2025.

Understanding how that process will work in practice is essential.

The next section moves from statute to operations.

Identity Verification in Practice

How Directors and PSCs Will Be Verified from November 2025

The introduction of mandatory identity verification represents the most tangible and operationally significant element of the Companies House reform. While the legislative intent is clear, its real impact will be determined by how verification functions in practice, how companies interact with the system, and where friction points emerge.

This section examines the identity verification framework as it will operate on the ground — not as an abstract policy concept, but as a procedural gatekeeping mechanism embedded into corporate life cycles.

Identity Verification: Who Must Verify and Why

| Role | Verification Required | Reason |

| Company Director | Yes | Exercises statutory control |

| Person with Significant Control (PSC) | Yes | Exercises effective control |

| Filing Presenter | Yes | Prevents anonymous submissions |

| Authorised Corporate Service Provider | Yes | Delegated verification responsibility |

| Company (as legal entity) | No | Verification applies to individuals |

Who Will Be Required to Verify Their Identity

Under the reformed regime, identity verification is not limited to new incorporations. It applies across the corporate ecosystem.

Verification requirements extend to:

- all company directors (including de facto and shadow directors where applicable),

- persons with significant control (PSCs),

- individuals submitting filings on behalf of companies where acting as agents,

- and, over time, existing officeholders appointed prior to the reform.

This universality is deliberate.

The objective is not merely to prevent new abuse, but to cleanse and stabilise the existing register by ensuring that individuals already exercising control are verifiably real and accountable.

Verification as a Status, Not a One-Off Event

One of the most misunderstood aspects of the reform is the nature of verification itself.

Identity verification is not conceived as a single transactional step. Instead, it establishes a verified status that attaches to an individual across their interactions with Companies House.

Once verified, an individual will be able to:

- act as a director of multiple companies,

- be declared as a PSC across different entities,

- and submit or authorise filings (subject to role and permissions),

without repeating the process each time — unless verification expires, is withdrawn, or becomes invalid due to changed circumstances.

This approach reflects a shift from document-based compliance to identity-based governance.

Two Routes to Verification: Direct and Agent-Assisted

The system provides two primary routes through which individuals can verify their identity.

Direct Verification via Companies House

Individuals may verify their identity directly through Companies House using digital tools. This route is expected to involve:

- submission of personal identification data,

- biometric or document-based checks,

- and automated cross-referencing against trusted data sources.

While designed for accessibility, this route assumes a level of digital literacy and access that may not be universal.

Verification via Authorised Corporate Service Providers

Alternatively, individuals may verify their identity through an authorised intermediary.

Authorised Corporate Service Providers (ACSPs) will be permitted to conduct verification on behalf of their clients, provided they meet statutory authorisation requirements and retain evidence in accordance with regulatory standards.

This route shifts part of the compliance burden to professional advisers — but it also concentrates responsibility and risk.

Evidence, Assurance, and Audit Trails

Verification is not merely declarative.

Evidence collected during the process must:

- satisfy statutory criteria,

- be capable of audit or review,

- and support downstream enforcement where inconsistencies emerge.

The existence of an evidence trail is a crucial departure from previous practice. It enables:

- retrospective examination of filings,

- correlation across multiple companies,

- and targeted intervention where identity misuse is suspected.

In effect, identity becomes a regulatory anchor point — linking individuals, companies, and activities in a way that was previously impossible.

Phased Rollout: Managing Scale and Transition Risk

The identity verification requirement will be introduced through a phased rollout, spanning approximately twelve months from November 2025.

This phased approach reflects practical realities:

- the sheer number of individuals listed on the register,

- the diversity of corporate structures,

- and the need to avoid systemic overload.

However, phased does not mean optional.

Companies will be required to ensure that relevant individuals complete verification within prescribed timeframes, particularly when:

- appointing new directors,

- updating PSC information,

- or making other substantive filings.

Delays or failures to comply will increasingly result in process blockage, rather than retrospective penalties.

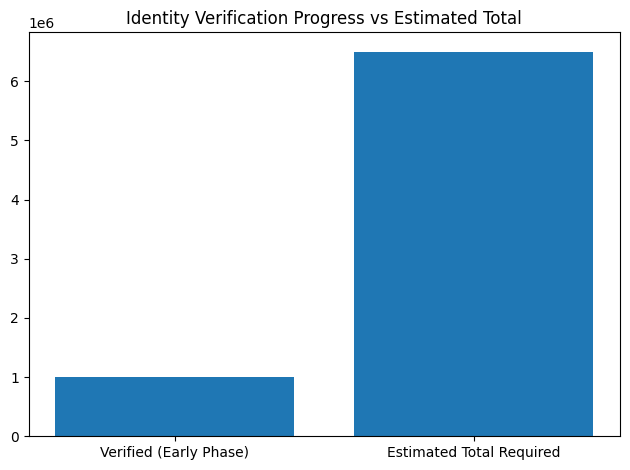

Figure 2 highlights the scale of the identity verification challenge. While early adoption demonstrates operational feasibility, the data also shows that the majority of affected individuals have yet to complete verification. This gap explains why Companies House has adopted a phased, functionality-based enforcement model rather than immediate sanctions.

What Happens If Verification Is Not Completed

One of the most significant behavioural levers embedded in the reform is the consequence of non-verification.

Rather than relying primarily on fines or criminal sanctions, the system is designed to withhold functionality.

Where verification requirements are not met:

- filings may be rejected,

- appointments may not be registered,

- and companies may be unable to complete statutory actions.

This approach reframes compliance as a prerequisite for participation, rather than a risk to be managed after the fact.

Identity Verification and Corporate Control

The introduction of verification fundamentally changes how corporate control is conceptualised.

Control is no longer defined solely by legal rights or shareholding percentages. It is also defined by verified personal accountability.

This has particular implications for:

- complex ownership chains,

- international structures,

- nominee arrangements,

- and historic PSC declarations that were never independently tested.

Where control cannot be mapped to a verified individual, regulatory tolerance will diminish.

Anticipated Friction Points and Bottlenecks

While the system is designed for robustness, it will not be frictionless.

Based on the structure of the reform, likely pressure points include:

- legacy companies with outdated or inaccurate records,

- individuals resident outside the UK with limited access to digital verification tools,

- structures relying heavily on nominees or corporate directors,

- and mass filings by agents during peak transition periods.

These friction points are not incidental. They are signals of areas where historical practices diverge from the new compliance model.

Why Verification Changes Corporate Behaviour

The long-term significance of identity verification lies not only in preventing abuse, but in reshaping incentives.

When identity is verified:

- anonymity loses value,

- accountability increases,

- and the cost of misrepresentation rises.

Over time, this is expected to alter how companies are structured, how advisers operate, and how risk is assessed across the UK corporate environment.

From Process to Power: Verification as an Enforcement Tool

Verification does not exist in isolation.

It feeds directly into the registrar’s expanded powers to:

- cross-check information,

- identify patterns of misuse,

- and intervene earlier and more decisively.

Understanding this interaction is essential.

The next section examines how these new powers operate — and how Companies House transitions from an information recipient to an active regulator with discretion and teeth.

New Powers of Companies House

From Data Custodian to Active Gatekeeper of Corporate Integrity

The reform of Companies House is not limited to identity verification. Verification is merely the entry point. The deeper and more consequential change lies in the new discretionary and enforcement powers granted to the registrar.

For the first time in its history, Companies House is being positioned as an active gatekeeper — not only of access to the register, but of the quality and legitimacy of the corporate data ecosystem as a whole.

This represents a structural rebalancing of power between companies and the state.

The End of Automatic Acceptance

Under the previous regime, Companies House was legally constrained to accept filings that met formal requirements. Submissions could be implausible, contradictory, or obviously fabricated — yet still accepted if they complied with formatting rules.

That constraint has now been lifted.

The registrar is empowered to:

- query information that appears inconsistent or suspicious,

- require clarification or supporting evidence,

- reject filings that do not meet substantive standards,

- and pause corporate actions until concerns are resolved.

This transforms filing from an administrative routine into a regulated interaction.

The Power to Query: A Subtle but Transformative Tool

One of the most important new powers is the authority to query information.

Unlike outright rejection, a query introduces friction without immediate sanction. It:

- forces engagement,

- requires explanation,

- and creates an audit trail.

From a regulatory perspective, this is a powerful mechanism. It allows Companies House to:

- identify patterns across filings,

- compare disclosures across related entities,

- and escalate concerns incrementally rather than reactively.

For companies, queries introduce a new compliance dynamic: silence or delay is no longer neutral.

Rejecting Filings: When Procedure Meets Substance

The ability to reject filings on substantive grounds represents a fundamental change.

Rejection may occur where:

- identity verification is incomplete,

- information conflicts with existing records,

- statutory requirements are not meaningfully satisfied,

- or there are indicators of misuse.

Importantly, rejection does not merely delay disclosure. It can block corporate actions, including:

- director appointments,

- changes in control,

- and other legally significant events.

In this way, compliance becomes a precondition for corporate mobility.

Retrospective Intervention: Cleaning the Existing Register

The registrar’s powers are not confined to future filings.

The ECCT Act enables Companies House to:

- annotate existing entries,

- remove information found to be incorrect or fraudulent,

- and require companies to correct historical inaccuracies.

This retrospective capability is critical.

Without it, the reform would address future risk while leaving legacy vulnerabilities intact. With it, the register becomes a living system, subject to continuous improvement and correction.

Registered Office Addresses: Enforcing Physical Credibility

The tightening of registered office requirements gives Companies House leverage over one of the most commonly abused elements of corporate identity.

The registrar may now challenge addresses that:

- lack a demonstrable connection to the company,

- cannot reliably receive official communications,

- or are associated with patterns of misuse.

Where an address is deemed inappropriate, Companies House can require rectification — and ultimately impose consequences for non-compliance.

This is not merely administrative housekeeping. Address credibility is a proxy for corporate substance.

Email Address and Contactability: Ending Corporate Silence

The introduction of a mandatory registered email address reinforces the expectation that companies must be contactable.

Failure to engage with Companies House communications will increasingly carry consequences, particularly where queries or compliance requests are ignored.

In practice, this reduces the feasibility of:

- dormant shell structures,

- “fire-and-forget” incorporations,

- and entities designed to evade accountability through non-responsiveness.

Lawful Purpose and Enforcement Optionality

The lawful purpose statement, combined with expanded powers, introduces a flexible enforcement mechanism.

Where evidence later suggests misuse:

- the original lawful purpose declaration can be revisited,

- discrepancies can form the basis for regulatory action,

- and intent becomes a factor in assessing compliance failures.

This elevates company formation from a purely mechanical act to a conditional authorisation.

Discretion, Not Automation: A Deliberate Design Choice

It is important to note that these powers are discretionary, not automatic.

The system is not designed to reject filings en masse. It is designed to:

- identify anomalies,

- prioritise risk,

- and intervene selectively.

This discretion allows Companies House to balance:

- efficiency and enforcement,

- business continuity and regulatory integrity.

However, discretion also introduces uncertainty — and uncertainty changes behaviour.

Behavioural Impact: Compliance Through Friction

The cumulative effect of these powers is not punitive. It is behavioural.

When filings can be questioned, rejected, or delayed:

- accuracy becomes valuable,

- preparation becomes essential,

- and casual non-compliance becomes costly.

For many businesses, the most significant impact will not be sanctions — but time, disruption, and reputational exposure.

From Gatekeeper to Intelligence Node

With identity verification, query powers, and retrospective intervention, Companies House begins to function as more than a registrar.

It becomes an intelligence node within the broader economic crime framework:

- correlating data across companies,

- identifying networks of control,

- and supporting downstream enforcement by other agencies.

This systemic role magnifies the importance of getting things right at the point of filing.

Preparing for a More Assertive Registrar

For companies and advisers, the message is clear.

The registrar is no longer a silent counterparty.

It is an active participant with expectations, discretion, and authority.

Understanding how this power will be exercised is essential — but equally important is understanding why these changes were made and what the government expects to achieve.

That requires a closer look at the data.

What the Official Data Reveals

Corporate Misuse, Economic Crime, and the Evidence Behind Reform

Regulatory reform of this scale does not occur in a vacuum. It is almost always preceded by an accumulation of evidence — data points that, taken together, demonstrate systemic failure rather than isolated abuse.

In the case of Companies House, the UK government’s own publications reveal a consistent and increasingly troubling picture:

corporate structures registered in the UK have been repeatedly used as tools of economic crime, facilitated by weaknesses in identity verification and data integrity.

This section examines what official data sources actually show — and how they were used to justify the transformation of the corporate register.

The Corporate Register as an Economic Crime Enabler

Government impact assessments and policy papers published in the years preceding the ECCT Act repeatedly highlight the same concern:

UK-registered companies were being exploited at scale because the system made exploitation cheap, fast, and low-risk.

Key characteristics identified by official sources include:

- ease of incorporation with minimal checks,

- absence of identity verification for controllers,

- low probability of detection at the point of entry,

- and limited consequences for submitting false information.

These characteristics did not merely coexist with economic crime — they enabled it.

Patterns Identified in Official Reviews

Across multiple government reviews and parliamentary briefings, recurring data patterns emerged.

Among the most frequently cited issues:

- thousands of companies registered to single addresses with no plausible operational capacity;

- directors listed across hundreds or even thousands of companies;

- repeated use of obviously fictitious names or improbable personal details;

- PSC declarations that failed to clarify who actually controlled the entity.

These were not anecdotal observations. They were supported by internal analysis of register data and corroborated by enforcement agencies.

The Scale of the Problem: Why Incremental Enforcement Failed

One of the most striking conclusions in government documentation is not simply that misuse occurred — but that manual enforcement could never keep pace with scale.

With millions of active companies on the register and hundreds of thousands of filings submitted annually, the registrar lacked:

- the authority to intervene early,

- the tools to verify identities at scale,

- and the mandate to prioritise data quality over speed.

This mismatch between volume and oversight created a structural enforcement gap.

In such an environment, enforcement after incorporation became both inefficient and reactive — often occurring only after significant harm had already taken place.

Data Quality as a Systemic Risk

A recurring theme in official analysis is the recognition that poor data quality itself constitutes a risk.

Inaccurate or misleading register data:

- undermines due diligence by banks and counterparties,

- weakens AML and KYC processes across the financial system,

- and allows illicit activity to masquerade as legitimate commerce.

In this sense, the corporate register does not merely reflect economic activity — it shapes it.

A register that cannot be trusted becomes a liability rather than a public good.

International Context and Comparative Pressure

The UK’s data did not exist in isolation.

International evaluations increasingly compared corporate transparency frameworks across jurisdictions, highlighting discrepancies in:

- beneficial ownership verification,

- enforcement powers of registrars,

- and mechanisms to prevent misuse at incorporation.

In several comparative assessments, the UK was identified as having strong disclosure requirements on paper, but weak verification mechanisms in practice.

This gap carried reputational consequences — particularly given the UK’s role as a global financial centre.

From Evidence to Policy Design

The ECCT Act reflects a clear policy conclusion drawn from this data:

If economic crime is facilitated at the point of incorporation,

then prevention must also begin at the point of incorporation.

This logic explains why the reform prioritises:

- identity verification before control is exercised,

- intervention before harm occurs,

- and data integrity as a foundational objective.

Rather than attempting to police misuse after the fact, the system is redesigned to make misuse harder to initiate.

Preparing the Ground for Visual Analysis

The data underpinning these conclusions lends itself to visualisation.

In later sections of this report, we will examine:

- timelines showing the escalation of reform measures,

- structural diagrams comparing the pre- and post-reform register,

- and matrices mapping compliance obligations across roles.

These visuals are not illustrative extras. They are analytical tools — intended to clarify how systemic risk translated into systemic reform.

What the Data Does Not Say

It is equally important to note what the official data does not suggest.

The reform is not predicated on the assumption that most companies are engaged in wrongdoing. Rather, it reflects recognition that a minority of abusive actors can impose disproportionate systemic risk when controls are weak.

The objective, therefore, is not to burden legitimate business — but to eliminate the structural conditions that allowed misuse to thrive.

From Diagnosis to Consequences

If the data explains why reform was necessary, the next question is unavoidable:

What will this reform actually change for businesses in practice?

The answer lies not only in law and process, but in risk distribution — who bears new obligations, where failure points arise, and how compliance costs shift across the corporate landscape.

That is the focus of the next section.

Practical Risk Implications for UK Companies

Where Compliance Will Break First — and Why

Regulatory reform rarely fails because of its stated objectives. It fails at the points where legal theory collides with operational reality.

The transformation of Companies House introduces a compliance framework that is coherent in design but uneven in its impact. Some companies will adapt with minimal disruption. Others will encounter significant friction — not because they are engaged in wrongdoing, but because their existing structures were built for a different regulatory era.

This section examines where, in practical terms, compliance stress is most likely to emerge.

Legacy Companies and the Burden of Historical Inaccuracy

One of the most underestimated risk factors lies in the age of corporate data.

Many UK companies — particularly those incorporated years or decades ago — operate with:

- outdated director details,

- incomplete PSC records,

- historic nominee arrangements,

- and registered office addresses that no longer reflect operational reality.

Under the previous regime, these inaccuracies were often tolerated as administrative imperfections.

Under the new framework, they become regulatory liabilities.

Identity verification forces a confrontation with historical data quality. Where discrepancies surface, companies may find themselves required to:

- correct legacy records,

- explain past filings,

- or restructure governance arrangements that no longer meet verification standards.

Directors and PSCs Outside the UK

Internationalisation introduces another layer of complexity.

Companies with:

- non-UK resident directors,

- overseas beneficial owners,

- or cross-border control structures,

will face additional practical challenges during verification.

These may include:

- limited access to UK-compatible digital verification tools,

- delays caused by document authentication,

- and coordination issues across jurisdictions.

While the system allows for agent-assisted verification, this shifts responsibility rather than eliminating risk.

Nominee Structures Under Scrutiny

Nominee arrangements are not unlawful. However, they are inherently sensitive to reforms centred on transparency and identity.

Where nominees:

- act as directors across multiple entities,

- represent layered ownership structures,

- or obscure effective control,

identity verification and enhanced registrar scrutiny may expose weaknesses that were previously tolerated.

In particular, PSC declarations that rely on formalistic interpretations rather than substantive control are likely to attract attention.

Agents, Intermediaries, and Delegated Risk

Many companies have historically relied on third-party agents to manage filings and corporate maintenance.

Under the new regime:

- only authorised service providers will be able to submit filings,

- agents will be required to verify identities and retain evidence,

- and failures by agents may directly impact their clients.

This reallocation of responsibility creates a new category of risk: delegated compliance failure.

Companies that treat agent selection as a cost decision rather than a risk decision may find themselves exposed to disruptions beyond their immediate control.

Process Blockage as the Primary Enforcement Tool

A defining feature of the new system is its reliance on process blockage rather than punishment.

Where compliance requirements are not met:

- filings are delayed or rejected,

- corporate actions are stalled,

- statutory changes cannot be completed.

For many businesses, the most significant impact will not be fines — but operational paralysis.

This is particularly acute in scenarios involving:

- urgent director changes,

- time-sensitive transactions,

- or regulatory filings linked to external deadlines.

Reputational and Transactional Consequences

Beyond immediate operational issues, compliance failures may have secondary effects.

Delayed or questioned filings can:

- raise red flags during due diligence,

- complicate financing or investment rounds,

- and undermine confidence among counterparties.

In a system where register data is expected to be accurate and verified, inconsistencies become more conspicuous — and more consequential.

Compliance Is No Longer Static

Perhaps the most profound change introduced by the reform is the shift from static to dynamic compliance.

Previously, many companies treated Companies House filings as periodic obligations. Under the new regime:

- data accuracy is continuous,

- identity status must be maintained,

- and changes trigger verification dependencies.

Compliance becomes an ongoing process rather than an annual exercise.

Early Indicators of Stress Points

Based on the structure of the reform, the earliest pressure points are likely to emerge in:

- companies with complex ownership chains,

- businesses reliant on historic nominee practices,

- structures with frequent governance changes,

- and entities that have deprioritised corporate housekeeping.

These are not marginal cases. They represent a significant portion of the UK corporate population.

From Risk Identification to Risk Management

Identifying risk is only the first step.

The next question — and the one most relevant to legitimate businesses — is how these risks can be systematically mitigated before they materialise as disruption.

That requires moving from analysis to preparation.

Common Failure Scenarios and Predictable Mistakes

What Companies Are Most Likely to Get Wrong in 2025–2026

Large-scale regulatory reforms rarely fail because businesses oppose them. They fail because implementation assumptions collide with organisational habits.

The reform of Companies House is no exception.

Despite extensive guidance and a phased rollout, the structure of the new system makes certain errors not only possible, but highly predictable. These errors will not be evenly distributed across the corporate landscape. They will cluster around specific behaviours, legacy practices, and decision-making shortcuts.

This section identifies the most likely failure scenarios — not as hypotheticals, but as patterns that follow logically from the design of the reform.

Mistake One: Treating Identity Verification as a Future Problem

One of the most common and consequential errors will be strategic procrastination.

Many companies will assume that:

- phased rollout implies low urgency,

- enforcement will be lenient during transition,

- or identity verification can be addressed reactively.

This assumption is flawed.

Because identity verification is tied to functional access to the register, companies that delay preparation may find themselves unable to:

- appoint directors,

- update PSC details,

- or complete routine filings when needed.

The cost of delay will not be punitive — it will be operational.

Mistake Two: Assuming Legacy Data Will “Carry Over”

Another predictable error is the assumption that historical filings will remain acceptable unless explicitly challenged.

In reality, the reform is designed to surface inconsistencies.

Where identity verification exposes:

- mismatched personal details,

- outdated control declarations,

- or implausible governance arrangements,

companies may be required to reconcile past filings with present standards.

For organisations that have accumulated years of administrative shortcuts, this reconciliation may be complex and disruptive.

Mistake Three: Underestimating the PSC Definition

The PSC regime has always been conceptually demanding. Under the new framework, its importance increases dramatically.

Companies that rely on:

- formal shareholding thresholds alone,

- contractual interpretations divorced from practical control,

- or generic nominee disclosures,

may find that their PSC declarations do not withstand scrutiny once identity and control are examined together.

This is particularly relevant for:

- family-owned businesses,

- investor-backed companies,

- and groups with layered ownership.

Mistake Four: Over-Reliance on Agents Without Oversight

The introduction of Authorised Corporate Service Providers will professionalise parts of the system — but it will not eliminate client responsibility.

Companies that:

- delegate verification entirely,

- fail to understand what their agent is doing,

- or choose providers based solely on cost,

may discover that agent failures translate directly into filing delays or compliance breaches.

Authorisation does not equal immunity.

Mistake Five: Treating Registered Office Requirements as Formalities

Registered office compliance has historically been treated as a low-risk administrative task.

Under the reformed regime, it becomes a credibility signal.

Addresses that:

- lack a genuine connection to the company,

- are shared at implausible scale,

- or fail to reliably receive communications,

are likely to attract scrutiny.

Companies that do not reassess their registered office arrangements may find themselves forced into rapid changes at inconvenient times.

Mistake Six: Ignoring the Behavioural Shift

Perhaps the most subtle error will be cultural.

The reform signals a shift from:

- tolerance of ambiguity

to - expectation of clarity.

Companies that continue to treat corporate filings as box-ticking exercises will struggle in a system that:

- prioritises coherence over speed,

- accuracy over convenience,

- and traceability over discretion.

Compliance is no longer episodic. It is behavioural.

Mistake Seven: Failing to Coordinate Across Functions

In many organisations, Companies House filings sit at the intersection of:

- legal,

- finance,

- tax,

- and corporate governance.

Where these functions operate in silos, inconsistencies are likely to emerge.

Identity verification, PSC accuracy, and lawful purpose declarations all require cross-functional alignment.

Failure to coordinate internally will become externally visible.

Why These Mistakes Matter More Than Before

Under the previous regime, many of these errors would have gone unnoticed or unaddressed.

Under the new framework:

- they trigger queries,

- block filings,

- or escalate scrutiny.

The system is designed not to punish ignorance, but to surface misalignment.

For companies that prepare, this creates clarity.

For those that do not, it creates friction.

Learning from Predictable Failure

The value of identifying predictable mistakes lies not in assigning blame, but in preventing disruption.

Each of the scenarios outlined above is manageable — if addressed early.

That raises the next logical question:

What should a well-prepared company actually do, step by step, before November 2025?

The answer lies in structured preparation.

Step Eight: Document Rationale, Not Just Outcomes

In a system that allows for registrar queries, documentation matters.

Companies should be able to explain:

- why control is structured in a particular way,

- how decisions are made,

- and why disclosures accurately reflect reality.

This does not require extensive narrative — but it does require intentionality.

Preparation as Risk Management, Not Burden

When approached strategically, preparation for the new Companies House regime is not merely defensive.

It can:

- reduce uncertainty,

- improve internal clarity,

- and strengthen external credibility.

Companies that invest in preparation early will not only avoid disruption — they will operate more confidently in a regulatory environment that increasingly rewards transparency and coherence.

The Role of Professional Judgment

It is important to emphasise that no checklist can replace professional judgment.

The reform introduces discretion — both for the registrar and for those navigating compliance.

Understanding when to correct, when to restructure, and when to explain requires expertise that sits at the intersection of:

- company law,

- tax,

- accounting,

- and regulatory practice.

From Preparation to Systemic Impact

Preparation at the company level aggregates into impact at the system level.

As more entities align with the new standards, the register itself becomes:

- more reliable,

- more useful,

- and more credible.

This is not incidental. It is the reform’s intended outcome.

The final analytical question, therefore, is broader:

What does this transformation mean for the UK business environment as a whole?

The Broader Impact

How the Companies House Reform Will Reshape the UK Business Environment

Regulatory reforms of corporate infrastructure rarely produce immediate, dramatic effects. Their true impact emerges gradually — through changes in behaviour, incentives, and market expectations.

The transformation of the UK corporate register is no exception.

While much of the public discussion has focused on fraud prevention, the longer-term implications of the reform extend well beyond economic crime. They affect how trust is established, how transactions are evaluated, and how the UK positions itself as a place to do business in an increasingly scrutinised global economy.

From Low-Friction Entry to Conditional Access

Historically, the UK’s competitive advantage lay in ease of entry.

Incorporation was fast, inexpensive, and procedurally simple. That ease attracted entrepreneurs — but it also attracted actors whose objectives were incompatible with transparency.

The reform recalibrates this balance.

Access to the corporate form is no longer unconditional. It is contingent upon:

- verified identity,

- coherent disclosure of control,

- lawful intent,

- and ongoing data integrity.

This does not eliminate ease of doing business — but it reframes it. The UK remains accessible, but no longer indifferent to who is entering and why.

A Shift in the Economics of Abuse

One of the most significant systemic effects of the reform is the alteration of cost-benefit calculations for abusive actors.

Previously:

- incorporation was cheap,

- identities could be fabricated,

- and detection risk at entry was minimal.

Under the new regime:

- identities must be verified,

- filings may be questioned,

- and inconsistencies create friction and traceability.

This does not eliminate abuse entirely — no system can — but it raises the cost and lowers the scalability of misuse.

In economic crime, marginal cost matters.

Increased Reliability of Corporate Data

As identity verification and data scrutiny take effect, the quality of information on the register is expected to improve incrementally.

This has secondary effects across the economy.

Reliable register data supports:

- more effective due diligence,

- more efficient credit assessment,

- reduced onboarding friction with banks and counterparties,

- and improved confidence in transactional contexts.

In this sense, the reform enhances not only regulatory integrity, but market efficiency.

Rebalancing Responsibility Across the Ecosystem

Another systemic shift concerns responsibility.

Under the old model:

- the state accepted information,

- third parties compensated through their own checks,

- and risk was diffused.

Under the new model:

- responsibility is more clearly allocated,

- accountability is traceable to individuals,

- and intermediaries operate under defined authorisation.

This rebalancing reduces ambiguity — but it also raises expectations of professionalism.

Implications for International Business and Investment

For international investors and counterparties, the reform sends a clear signal.

UK-incorporated entities are no longer assumed to be transparent merely because they are registered. They are expected to be verifiable.

Over time, this may:

- increase confidence in UK entities abroad,

- simplify cross-border compliance assessments,

- and strengthen the UK’s position in negotiations around corporate transparency standards.

In a global environment where regulatory credibility increasingly influences capital flows, this signal matters.

Short-Term Friction, Long-Term Stability

No reform of this magnitude is frictionless.

In the short term, businesses will experience:

- adjustment costs,

- learning curves,

- and occasional disruption.

However, systemic stability is rarely achieved without transitional discomfort.

The strategic objective is not perfection, but resilience — a corporate infrastructure capable of supporting legitimate business without enabling systemic misuse.

A Cultural Shift in Corporate Governance

Perhaps the most enduring impact of the reform will be cultural.

When identity, control, and purpose are treated as verifiable facts rather than formal declarations, governance practices evolve.

Over time, companies are likely to:

- document decisions more carefully,

- clarify control structures proactively,

- and treat corporate filings as extensions of governance rather than compliance chores.

This cultural shift aligns UK corporate practice more closely with its stated values of transparency and accountability.

What This Means for Professional Services

The reform also reshapes the role of advisers.

Professional services move from:

- transactional support

to - risk-informed guidance.

Accounting, tax, and corporate advisory functions become more integrated — because inconsistencies across these domains are increasingly visible.

For firms that embrace this integration, the reform creates opportunity rather than burden.

The Direction of Travel Is Clear

While implementation details will evolve, the direction of travel is unmistakable.

The UK corporate register is becoming:

- more assertive,

- more intelligent,

- and more consequential.

Businesses that align early will operate with greater certainty. Those that resist or delay will encounter friction not as punishment, but as a natural consequence of misalignment.

From Systemic Impact to Evidence-Based Conclusions

At this stage of the investigation, the contours of the reform are clear.

What remains is to:

- synthesise the findings,

- anchor them explicitly in evidence,

- and present the conclusions in a form that is both analytical and actionable.

The final sections of this report will therefore focus on:

- visualising the reform through data and timelines,

- summarising evidence-based conclusions,

- and articulating the role of structured professional support in the new environment.

Data Visualisation and Analytical Models

Transition Plan: Key Milestones and Obligations

| Phase | Date | Who is affected | Practical impact |

| Voluntary verification | Apr–Nov 2025 | Directors / PSCs | Early compliance, low friction |

| Mandatory for new roles | 18 Nov 2025 | New directors & PSCs | Appointments blocked without ID |

| Existing roles | 2025–2026 | Existing directors & PSCs | Filing restrictions |

| Full transition | End 2026 | All relevant persons | Normalised enforcement |

How the Reform Can Be Understood Through Timelines, Matrices, and Structural Comparisons

Complex regulatory change becomes intelligible only when it is made visible.

The reform of Companies House introduces multiple layers of change — legal, procedural, behavioural — unfolding over time and affecting different actors in different ways. Text alone is insufficient to capture these interactions.

This section sets out the core analytical visualisations that underpin this investigation. Each is derived from official guidance, statutory documentation, and implementation schedules, and each serves a distinct analytical purpose.

Visual Model 1: Reform Timeline (2023–2026)

Purpose:

To demonstrate that the Companies House reform is not a single event, but a multi-year transformation with clearly defined phases.

Description:

A horizontal timeline beginning with the passage of the Economic Crime and Corporate Transparency Act and extending through the full rollout of identity verification.

Key milestones displayed:

- Passage of primary legislation

- Introduction of new registrar objectives

- Expansion of registrar powers

- Launch of identity verification (18 November 2025)

- 12-month phased transition for existing companies

- Full operational normalisation

Analytical value:

This timeline illustrates why postponement is a strategic error. Even though enforcement is phased, the direction of travel is irreversible, and preparation must precede deadlines.

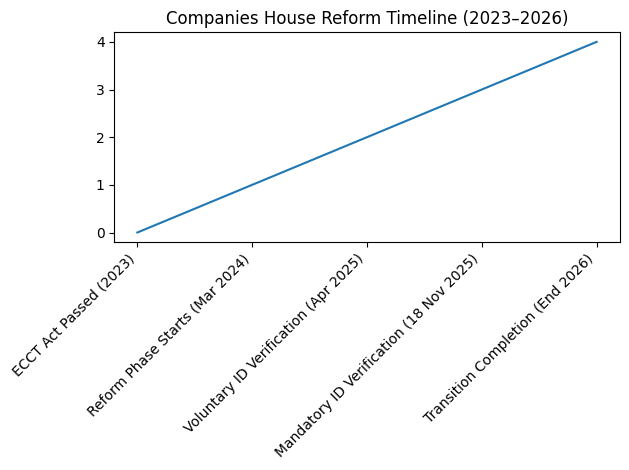

Figure 1 illustrates that the reform of Companies House is not a single regulatory event, but a multi-year structural transition. The introduction of mandatory identity verification in November 2025 represents only one milestone within a broader redesign that began in 2023 and will continue through 2026.

Visual Model 2: “Before vs After” — The Role of Companies House

Purpose:

To highlight the structural transformation of the registrar’s function.

Structure:

A two-column comparative table.

Before the reform:

- Passive recipient of filings

- No identity verification

- Limited power to question information

- Acceptance based on form, not substance

After the reform:

- Active gatekeeper of corporate data

- Mandatory identity verification

- Power to query, reject, and remove filings

- Substantive assessment of plausibility and coherence

Comparative Framework

| Before the Reform | After the Reform |

|---|---|

| Passive recipient of filings | Active gatekeeper of corporate data |

| No identity verification | Mandatory identity verification |

| Limited power to question information | Power to query, reject, and remove filings |

| Acceptance based on form, not substance | Substantive assessment of plausibility and coherence |

| Administrative function | Regulatory and enforcement-oriented function |

Analytical value:

This comparison demonstrates that the Companies House reform is not incremental.

It represents a paradigmatic shift from procedural registration to active regulatory control.

Visual Model 3: Identity Verification Flow Diagram

Purpose:

To explain how identity verification functions as a gatekeeping process, not a background check.

Structure:

A flow diagram beginning with an individual (director or PSC) and branching into two routes:

- Direct verification via Companies House

- Verification via an authorised service provider

Each route converges on a verified identity status, which then enables:

- appointment

- filing

- control declaration

Failure points are clearly marked, showing where process blockage occurs if verification is incomplete.

Analytical value:

This diagram demonstrates that verification is a functional dependency, not a compliance add-on.

Visual Model 4: Compliance Impact Matrix by Role

Purpose:

To show that the reform affects stakeholders asymmetrically.

Structure:

A matrix mapping roles against obligations.

Roles:

- Directors

- PSCs

- Company secretaries

- Authorised agents

- Companies as legal persons

Obligations:

- Identity verification

- Evidence retention

- Filing accuracy

- Responsiveness to queries

Responsibility Matrix

| Role | Identity Verification | Evidence Retention | Filing Accuracy | Responsiveness to Queries |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Directors | ✔ Required | ✖ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Persons with Significant Control (PSCs) | ✔ Required | ✖ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Company Secretaries | ✖ | ✖ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Authorised Agents | ✔ Required | ✔ Mandatory | ✔ | ✔ |

| Company (legal person) | ✖ | ✖ | ✔ | ✔ |

Analytical value:

This matrix dispels the misconception that compliance responsibility rests solely with companies.

Accountability is distributed, role-specific, and traceable.

Visual Model 5: Risk Escalation Pathway

Purpose:

To visualise how minor inaccuracies can escalate into significant disruption.

Structure:

A stepped diagram showing progression from:

- data inconsistency

→ registrar query

→ delayed response

→ filing rejection

→ operational blockage

Analytical value:

This model reframes compliance risk. The primary danger is not sanction, but loss of functional access.

Visual Model 6: Legacy Risk Concentration

Purpose:

To identify where reform pressure will concentrate first.

Structure:

A conceptual heat map highlighting:

- older companies

- complex ownership chains

- nominee-heavy structures

- frequent governance changes

Conceptual Risk Heat Map (Textual Representation)

| Structural Characteristic | Risk Intensity |

|---|---|

| Older companies with legacy filings | 🔴 High |

| Complex ownership chains | 🔴 High |

| Nominee-heavy governance structures | 🔴 High |

| Frequent director / PSC changes | 🟠 Medium–High |

| Recently incorporated, simple structures | 🟢 Low |

Key Insight:

Risk concentration correlates with structural complexity and legacy data, not company size or intent.

Analytical value:

This model supports the conclusion that reform impact will be asymmetric, clustering around specific structural profiles.

Companies House Reform: Statutory Transition Plan (2024–2026)

| Reform Phase | Key Date | Who Is Affected | Practical Consequences |

| ECCT Act enters implementation phase | March 2024 | All UK companies | Companies House mandate changes |

| Voluntary ID verification | April 2025 | Directors, PSCs | Early compliance possible |

| Mandatory ID verification (new roles) | 18 November 2025 | New directors & PSCs | Appointments blocked without ID |

| Mandatory verification (existing roles) | 2025–2026 | Existing directors & PSCs | Filing restrictions if unverified |

| Full operational normalisation | End of 2026 | All relevant persons | Verification embedded into all filings |

Why Visualisation Matters in Regulatory Analysis

These visual models are not decorative. They perform three critical functions:

- They translate statutory language into operational reality.

- They expose dependencies and failure points that text alone obscures.

- They allow decision-makers to assess exposure quickly and accurately.

For professional audiences, this distinction is crucial.

From Models to Conclusions

With the analytical framework now fully constructed — law, process, data, risk, preparation, and visualisation — the investigation reaches its final stage.

What remains is to draw evidence-based conclusions, without exaggeration or speculation, and to articulate what these findings mean for businesses navigating the new environment.

Evidence-Based Conclusions

What the Companies House Reform Ultimately Means for UK Companies

After examining the historical weaknesses of the UK corporate register, the statutory redesign introduced by the Economic Crime and Corporate Transparency Act, the mechanics of identity verification, and the practical risk implications for businesses, several conclusions emerge with clarity.

These conclusions are not speculative. They follow directly from the design of the reform, the official data that justified it, and the behavioural incentives embedded in the new system.

Conclusion One: The Reform Is Structural, Not Tactical

The transformation of Companies House is not a targeted response to a temporary spike in fraud. It is a structural re-engineering of corporate infrastructure.

The shift from:

- disclosure to verification,

- acceptance to scrutiny,

- and neutrality to gatekeeping

signals a permanent change in how the UK conceptualises corporate legitimacy.

Companies should not expect a return to the pre-reform environment. The legal and operational architecture has moved decisively beyond it.

Conclusion Two: Identity Has Become the Primary Unit of Accountability

For the first time in UK company law, identity functions as a regulatory control mechanism, not merely an attribute of disclosure.

Directors and PSCs are no longer abstract roles. They are verified individuals whose participation in corporate governance is conditional on traceable identity.

This has far-reaching implications:

- anonymity loses strategic value,

- nominee arrangements require substantive justification,

- and responsibility becomes increasingly personal rather than diffuse.

In this system, obscurity is not neutral — it is anomalous.

Conclusion Three: Compliance Risk Has Shifted from Penalties to Functionality

One of the most consequential findings of this investigation is the redefinition of compliance risk.

The reform does not primarily rely on:

- fines,

- criminal sanctions,

- or retrospective enforcement.

Instead, it operates through functional dependency.

Where requirements are not met:

- filings cannot proceed,

- corporate actions stall,

- and governance flexibility is lost.

For most legitimate businesses, this operational friction will matter far more than formal sanctions.

Conclusion Four: Legacy Data Is the Hidden Fault Line

The greatest source of future disruption is not new regulation — it is old information.

Companies that accumulated inaccuracies, shortcuts, or ambiguities under the previous regime will confront them when verification and scrutiny expose inconsistencies.

This does not imply wrongdoing. It reflects a mismatch between historical tolerance and current expectations.

Those who proactively reconcile legacy data will experience reform as manageable.

Those who do not will experience it as abrupt and disruptive.

Conclusion Five: The Reform Rewards Coherence, Not Scale

Contrary to some concerns, the reform does not inherently disadvantage small or growing businesses.

Its primary discriminator is coherence:

- alignment between legal form and actual control,

- consistency across filings,

- and clarity of purpose.

Large, complex organisations with fragmented governance may face more difficulty than smaller companies with transparent structures.

Size is not the variable. Alignment is.

Conclusion Six: Professional Judgment Becomes More Valuable, Not Less

Automation and digital verification might suggest reduced need for professional input. The opposite is true.

As the system introduces:

- discretion,

- judgement-based queries,

- and contextual assessment,

the value of integrated legal, tax, and accounting insight increases.

Advisers are no longer simply facilitators of filings. They are interpreters of regulatory intent and managers of structural risk.

Conclusion Seven: The UK Is Trading Convenience for Credibility

At a macro level, the reform reflects a deliberate trade-off.

The UK is sacrificing a degree of frictionless incorporation in exchange for:

- improved data reliability,

- reduced systemic abuse,

- and enhanced international credibility.

This trade-off aligns with broader global trends in corporate transparency and economic crime prevention.

For legitimate business, credibility is an asset — not a burden.

Conclusion Eight: Early Adaptation Creates Strategic Advantage

Perhaps the most practical conclusion is also the simplest.

Companies that:

- prepare early,

- audit their structures honestly,

- and integrate verification into governance processes,

will encounter the reform as a normalisation, not a crisis.

They will:

- avoid last-minute disruption,

- present lower risk profiles to counterparties,

- and operate with greater confidence in a more exacting environment.

In regulatory transitions, timing is often decisive.

The Final Finding: This Is a Change in Corporate Culture

Beyond law, process, and data, the Companies House reform represents a cultural shift.

It moves UK corporate practice away from:

- minimal compliance

towards - demonstrable integrity.

In doing so, it aligns corporate registration with the realities of a financial system where trust must be earned, not assumed.

Closing Perspective

The UK corporate register is no longer merely a public record.

It is becoming an active instrument of governance.

For businesses willing to engage with this reality, the reform offers clarity and stability.

For those that resist, it introduces friction by design.

The direction is clear.

The evidence is documented.

The question for each company is not whether the reform will affect them — but how prepared they will be when it does.

Executive Summary

The Companies House Reform and What It Means for UK Business Leaders

This investigative report has examined the most significant reform of the UK corporate register in modern history. Drawing on statutory changes, official government analysis, and regulatory design logic, it reaches a clear and evidence-based conclusion:

The UK has fundamentally redefined what it means to operate a legitimate company.

The transformation of Companies House under the Economic Crime and Corporate Transparency Act is not an administrative update. It is a structural shift in how corporate legitimacy, accountability, and trust are established.

For business leaders, the implications are strategic rather than technical.

- The Nature of the Reform: Structural, Permanent, and Irreversible

The reform replaces a passive, disclosure-based registration system with an active, verification-driven model.

Historically, Companies House functioned as a repository of self-reported information. Under the new regime, it becomes a gatekeeper of corporate integrity, empowered to verify identities, question data, reject filings, and intervene proactively.

This shift is permanent.

There is no indication — legally or politically — that the UK intends to return to a system built on trust without verification.

For executives, this means that corporate compliance is no longer about meeting minimum filing requirements, but about maintaining ongoing alignment between reality and record.

- Identity as the New Foundation of Corporate Governance

Mandatory identity verification for directors and persons with significant control represents the most consequential operational change.

Identity is no longer a descriptive attribute.

It is now a precondition for participation in corporate governance.

This has several executive-level consequences:

- Control must be traceable to real, verifiable individuals.

- Nominee and layered structures must withstand scrutiny beyond formal legality.

- Ambiguity around “who is really in charge” becomes a risk factor, not a convenience.

For boards and owners, governance clarity is no longer optional — it is structurally enforced.

- The Real Compliance Risk: Operational Blockage, Not Penalties

One of the most important findings of this investigation is the nature of enforcement.

The reform does not rely primarily on fines or prosecutions.

Instead, it enforces compliance through functional dependency.

Where requirements are not met:

- filings are delayed or rejected,

- director appointments cannot be registered,

- corporate actions are stalled.

For businesses, the cost is not abstract legal exposure — it is loss of operational flexibility at critical moments.

This makes preparation a business continuity issue, not merely a legal one.

- Legacy Data Is the Main Exposure

The greatest source of disruption is not new regulation, but old information.

Many companies operate with:

- outdated director or PSC records,

- historic nominee arrangements,

- registered office structures designed for a lighter-touch regime.

Identity verification and enhanced scrutiny will surface these inconsistencies.

Companies that proactively audit and reconcile legacy data will experience reform as manageable.

Those that do not risk abrupt disruption when verification collides with historical inaccuracies.

- The Reform Rewards Coherence, Not Size

This reform does not target small businesses, nor does it inherently favour large ones.

Its primary discriminator is coherence:

- alignment between ownership, control, and disclosure;

- consistency across legal, tax, and accounting perspectives;

- clarity of purpose and governance.

Complexity without clarity is now a liability.

- Strategic Implications for Leadership

For boards, owners, and senior management, the reform demands a shift in mindset:

- Corporate filings are no longer administrative chores — they are governance artefacts.

- Compliance is no longer episodic — it is continuous.

- Transparency is no longer reputational — it is operational.

Executives who treat the reform as a technical matter risk underestimating its strategic impact.